Concrete scars on the border of the Pyrenees

- About to end the 1936 War, dictator Franco ordered the construction of thousands of bunker in the Pyrenees. We are used to seeing them on the mountain some time ago, but we did not know that they formed a great defensive line, and recovery initiatives have been launched in recent years. In fact, these concrete structures are not merely archaeological heritage, but places for the memory of the social and economic repression provoked by Franco in border villages.

80 years ago, in 1944, the Franco military wanted to create a solid and definitive defensive line that made it impossible to cross the Pyrenees. They designed the construction project of almost 10,000 bunkers and fortifications along the 500 kilometers of the mountain range. Although in the end they did not become half – in Navarre and Gipuzkoa, of the 2,884 bunkers initially planned, 1,836 ended, and in Catalonia 2,884 of the 5,800 bunkers – this pharaonic work left a deep scar on the border towns and society, where thousands of prisoners and soldiers worked in disastrous conditions.

This defence system has sometimes been given the name of line P, probably of the word Pyrenees, although it has never been officially called that. It had two phases: in the first, around 1939 and 1940, several strategic places of Gipuzkoa and Navarre were fortified under the orders of Colonel José Vallespín; in the second, which lasted from 1944 until the mid-1950s, extending throughout the Pyrenees under the motto of the Defensive Organization of the Pyrenees.

A psychological limit

Even if it sounds like a lie, even if it is thousands of military structures, until the end of the 1990s nothing was known about them, and today citizens are still surprised when they are surprised on mountain trips. According to many historians, in the context of the Second World War and during the Autarkic era, the Franco regime suffered a true psychosis in the face of “external” attacks, and the goal of the Bunkers was to prevent the invasion of troops, initially of the troops of the French republic, after the Nazis and finally of the allies.

On August 23, 1944, brigadier Antonio Barroso signed the order to create a bunker defense system, and two days later the allies liberated Paris. By then, thousands of Republican machines were in full organization to access Franco Spain from the Pyrenees, coordinated by the Pamplona chief of the PCE, Jesús Monzón. He was attacked in October 1944, mainly from Val D’Aran, but also from different points in Navarra. The operation was an absolute failure.

.jpg)

Franchises didn't invent anything with those bunkers. In the belligerent atmosphere of the time these lines were of great importance: a decade earlier the Maginot line was built in France near the border between Germany and Italy; the Soviet Union brought the Stalin line from the Baltic to the Black Sea; and Hitler’s Germany created the Atlantic wall over thousands of kilometres. In fact, in the project of the Pyrenean fortresses, the Franco was limited to using the same methodology used by the Nazis for the coast: nests for machine guns, underground steps, artillery points, etc., but unlike the Nazis, instead of doing so on a continuous line they were organized into “resistance points” or assemblies.

This impressive work cannot be remembered only from a strictly military point of view, among other things because it was soon seen to be totally sterile and useless. The military coup d’état of 1936 made it clear from the outset that after the war a “new Spain” would be built, with death, punishment and indoctrination. Because Franco had his main enemy inside, and the most effective way to pursue him was to force people to work until they were exhausted with azades and shovels. They therefore built not only a geographical border, but also a psychological border with this defensive system, with an ideological component highlighted in fascist Europe.

The "secret" of many decades

Due to its military nature, the Pyrenees Ombudsman, probably one of the largest public works in the twentieth century in the Spanish State, was “a secret” for decades, despite the fact that thousands of prisoners and soldiers were displaced. In Euskal Herria the last bunkers were built in 1958, a time from which it seems that they stopped drawing the line.

In 1955 Francoist Spain emerged from autarky and was admitted to the UN, so the threat of the “exterior” enemy no longer existed. That is what the official account says. But it was actually abandoned because it was a totally sterile military infrastructure, because it was “a carlist trench, but made in pieces,” as a commander confesses to Franco. However, the Spanish army continued to monitor the strengths in the 1960s and were completely abandoned only in 1986, when Spain entered NATO.

Despite being a work of Alimal, it has hardly been known by historiography. The first investigations were published in the late 1990s, but until recently it has not been possible to address seriously, among other things because until 2018 the documentation related to the line of defense has been classified as secret in military archives. That year, the Spanish Ministry of Defence, by decree, annulled the Official Secrets Act of 1968 in this case. According to the experts, the funds kept in Ávila can find a large amount of documentation that has not yet been investigated. The upper planes have been taken from them: one represents the defensive line of Erratzu and the other the one of Ibañeta.

“They had almost died more than alive”

In the construction of the first phase of the Pyrenean fortresses, the prisoners' labor force was mainly used, organized in the Workers' Battalions and in the Workers' Penal Battalions, those who led political dissidents and those who the regime considered "dangerous". It is believed that between 1939 and 1942 in the Pyrenees 20,000 people engaged in this type of slave, in very precarious conditions, to sleep in the miserable huts, to end hunger and to fear punishment.

The well-known anarchist leader Felix Padín described the situation perfectly in his memoirs: “For a while I had to go barefoot to work with my feet in pieces. Once again we were sent to search for firewood, with the snow to the waistline and we were incommunicado for seven days. Two companions flee, hide in a hut, but a shepherd goat teaches the guards and killed them right there. Then they brought the bodies to the people and trained us before them to see how they buried them.”

.jpg)

The defensive system was not limited to the bunkers, but it was also necessary to build roads and roads between valleys with great land movements. During these years, the Lesaka-Oiartzun, Irumaya-Eugi, Bidankoze-Igari and Lezo-Jaizkibel roads were opened, among others, in which workers were informed in the latter work under number 2.626 of ARGIA. In fact, Padín stayed on the road of Vidángoz and slept in the barracks of the upper Igari, along with some Andalusian prisoners: “The barracks were tired, stacked, they were much more hungry than we, without spirit, almost die of life.” Today you can see one of the barracks rebuilt on site and each year a tribute is celebrated by the Bideak Memory.

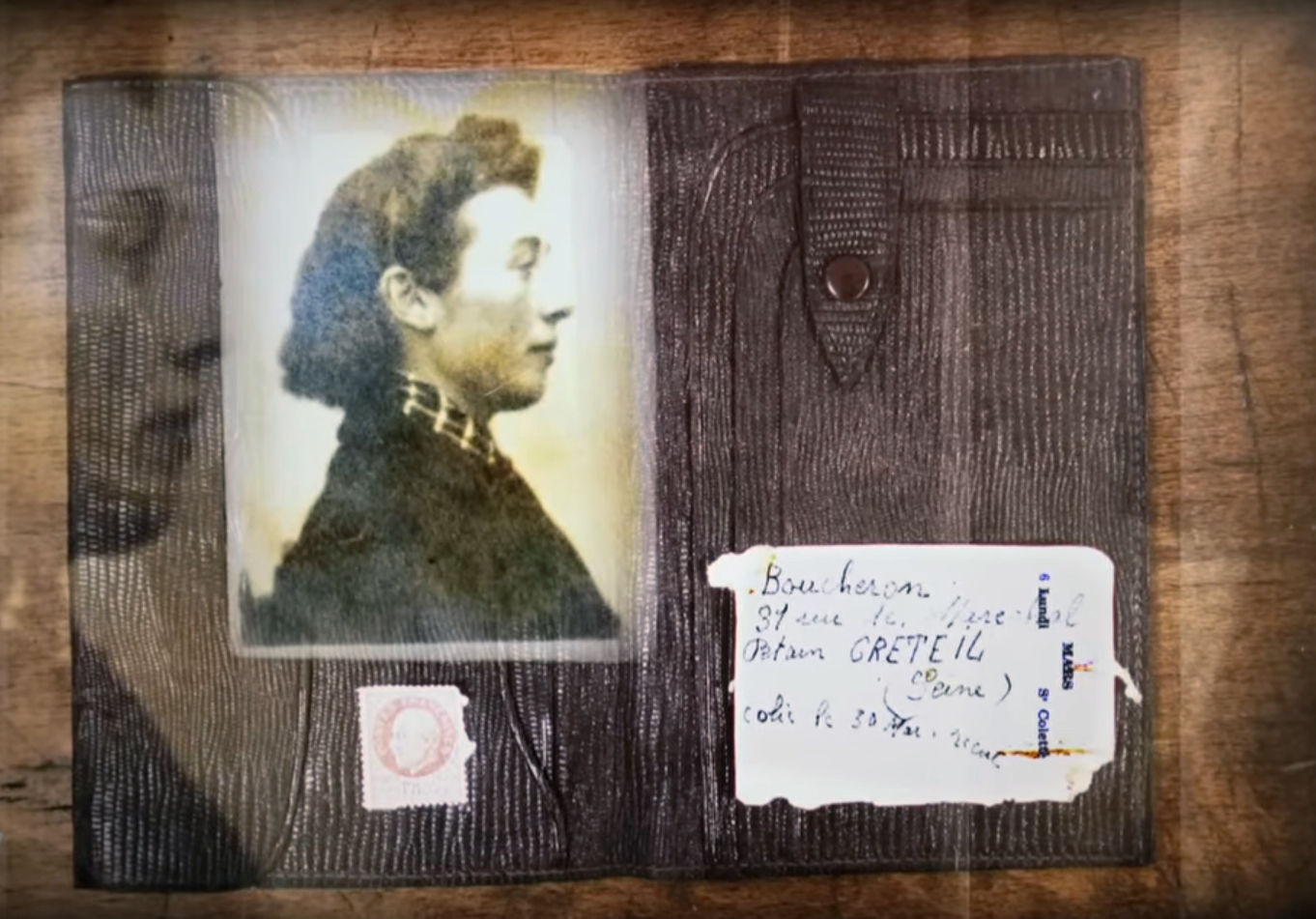

In the second phase, young people undergoing military service were used, recruits from 1940, 1941 and 1942. It was usually a two-year military service, but in that harsh post-war period they were three years old, not receiving “training”, but working for free. Thus, conditions were not much better than those of the prisoners’ battalions. According to archaeologists Carlos Zuza and Nicolas Zuazua, of Cabinet Trama, who have studied the subject in depth, in the soldiers' files one can observe the political control that was in them: “It’s classified as a thief. Aita has Marxist ideas,” you can read in one of the tiles.

Zuazua and Zuza have published the study in the journal of history and geography Huarte de San Juan de la Universidad Pública de Navarra, along with Professor Eduardo Arteta. They have investigated the cases of both Baztán and Auritz/Burguete and for this they have been exploring the military archive of Ávila, they say that there are many unseen materials.

.jpg)

“No excuses”

We are becoming increasingly aware of the archeology and punitive function of these structures, but it is not yet clear what the social and economic impact of the construction of bunkers was in the Pyrenean valleys. The villages in these valleys suffered the burden of keeping a large number of soldiers for more than twenty years.

Another consequence of this militarization was the continued occupation of public buildings.

Municipal archives can be a good source of knowledge about this local reality. In Auritz / Burguete, for example, researchers have found numerous complaints from citizens in the archive about cuts in rationing cards. According to a 1941 Civil Governor's order, headphones reduced their bread from 150 to 120 grams, which was already scarce: “Beraz, behar dugu (...) aitzaki bat suministre-pan (...) equizalo noralen lozas (...), eta 0.20 pesetas”, esaten du. As you can see, the sale of toast was measured rigorously.

Of course, in this situation many had no choice but to resort to straperture and smuggling. But to avoid this, the authorities further restricted the possibility of moving to the citizens and needed special permission to walk a “imaginary” line from Leitza to Liédena, signed by the military commander who was staying at the Hotel Loizu in Auritz. “The public phone was also removed from Secretary Faustino Irigaray’s house,” the researchers say, as a sign of the overwhelmed atmosphere in the UPNA article. Irigaray was reprimanded by the franchisees by a decree of confiscation of property.

In 1943 the entire territory, including Navarre and Gipuzkoa as a whole, which moved from the Pyrenees to the Ebro, was declared a “military zone” by the regime, which meant greater social control, but evidently control at the border reached its end. They came to form cattle censuses, cars and carriages in various localities, and they even asked mayors to capture flying pigeons.

An online map

On a map placed on the network you can see the location of all the Francoist bunkers located in the Pyrenees, in a project carried out in Catalan, Basque, French and Spanish: www.lineap.spiki.org. They are innumerable scientifically, marked with different symbols depending on their state or information.

In green, I'm sure where are the bunkers that we know and in yellow those that are dubious. In Euskal Herria, especially between Jaizkibel and the Peñas de Aia, between Baztán and Quintoa and Orreaga (in small image) are these strengths.

Looting of communal lands

The construction of highways and giant structures of concrete and iron required huge quantities of materials. The Quinto Real and Roncesvalles defenses project, for example, provided dozens of artillery batteries and hundreds of sinks and settlements, surrounded by 126 kilometres of trenches and 144 kilometres of fences. For this, 143,000 tables, 140,000 stakes and 8,384 tons of concrete were estimated.

Thus, in addition to the evident corruption in the diversion of money, it is not surprising that the exploitation of the existing forests in the communal lands is one of the main sources of conflict, since the military massively used their wood, essential for the local economy. Before building the Bidankonz road, the whole environment was covered with beech trees, but in just ten months it was completely clear.

Another consequence of this militarization was the constant occupation of public buildings. In the case of Roncal, the children had to leave school because they introduced a full battalion of prisoners. On the contrary, the army officers received guests in private houses and the military seized the stables for their crutches and mares, no matter how much the cattle of the citizens. “You did not send in anything, nor in things that were yours,” recalls María Jauregi, of Igari, for the exhibition “Concrete barriers”, organized by the Institute of Memory of the Government of Navarra.

In 1943 the territory of the Pyrenees to the Ebro was declared a "military zone" by the regime, which increased social control

Emerging concrete memory

This exhibition has been installed in 11 localities and places in Euskal Herria, as well as in Brussels and Portbou (Catalonia) and has been attended by expert researchers in the field such as Fernando Mendiola or Juan Carlos García Funes. This is not the only initiative that has recently been taken on bunkers. In Oiartzun, the Kattin Txiki association has rebuilt in the fort of Arkale a barracks used by workers in the post-war period; in Ochagavía the town hall has conditioned the bunker located in the vicinity of the Muskilda hermitage; and in other localities there have been talks, excursions and work fields.

Eleven Navarre routes through the Pyrenees

To publicize the repression of Franco after the War of 1936 and the slavery suffered by thousands of prisoners and soldiers, the Department of Memory and Coexistence of the Government of Navarra has developed numerous itineraries through the Pyrenees, within the project Concrete Borders.

The strengths and roads have been cleaned, marked and marked, and information panels have been put in place for people to know the facts. These include the roads of Lesaka-Oiartzun, Irumaya-Artesiaga, Igari and Vidángoz, and the bunkers of Bera, Legasa, Bertizarana, Muskilda, Erratzu and Otsondo.

The itineraries will be fully accessible and the materials have been produced by local companies. "In this way it will be possible to approach a repressive manifestation of the Franco regime," they explain.

Last summer, 25 young people worked on the arrangement of the bunkers headed from Isaba to Belagua and Belabartza within the Barriers of Concrete program of the Government of Navarra: “The fascisms and post-fascisms that are growing today seek to legitimize this terrorist policy, and young people have become protagonists in bringing forward the memory of the unjust violence of Franco’s regime,” said Ana Ollo, a member of the Memory and Coexistence Council of Navarra, during his visit to the field of work.

Auritz / Burguete is also working on the recovery of memory and Franco’s bunker, led by Aritz Gorostiaga, made a documentary in 2019 to tell the case of that town. The area of Auritz and Orreaga was one of the areas that built the most bunker: “The Roncesvalles pass was the first to be fortified with the Bidasoa to avoid a siege maneuver,” explains Carlos Zuza. García Funes also speaks in the documentary: “We must understand what it meant that at a time when citizens were suffering from lack of supply and difficulties, in the post-war period, a fortress of this kind was prioritized, which had no use over time.”

.jpg)

And today? Does this story have anything to do with the situation in many Pyrenean regions today? As has been denounced many times, in these territories affected by the depopulation, isolation and immense lack of service, one could think that the military control and looting that he had experienced for decades not only left a concrete scar, but a profound social footprint.

Salvador Puig Antich frankismoaren kontrako militantea izan zen. Askapen Mugimendu Iberikoko kidea, 1973ko irailaren 25ean atxilotu zuten. Gerra-kontseilua egin zioten, eta garrotez exekutatu zuten handik sei hilabetera, 1974ko martxoaren 2an. Aurtengo otsailean baliogabetu du... [+]

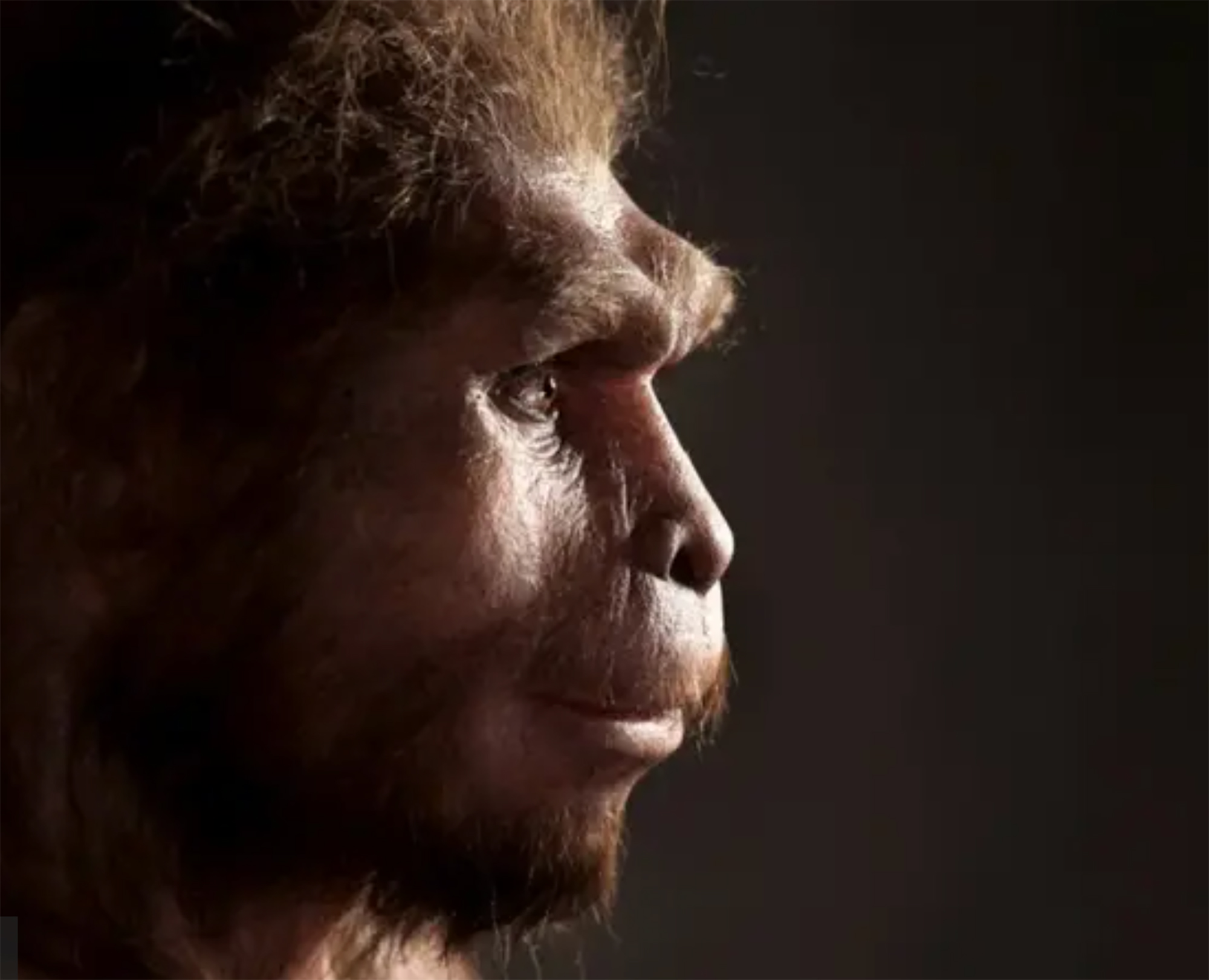

Rudolf Botha hizkuntzalari hegoafrikarrak hipotesi bat bota berri du Homo erectus-i buruz: espezieak ahozko komunikazio moduren bat garatu zuen duela milioi bat urte baino gehiago. Homo sapiens-a da, dakigunez, hitz egiteko gai den espezie bakarra eta, beraz, hortik... [+]

Böblingen, Holy Roman Empire, 12 May 1525. Georg Truchsess von Waldburg overthrew the Württemberg insurgent peasants. Three days later, on 15 May, Philip of Hesse and the Duke of Saxony joined forces to crush the Thuringian rebels in Frankenhausen, killing some 5,000 peasants... [+]

During the renovation of a sports field in the Simmering district of Vienna, a mass grave with 150 bodies was discovered in October 2024. They conclude that they were Roman legionnaires and A.D. They died around 100 years ago. Or rather, they were killed.

The bodies were buried... [+]

Washington, D.C., June 17, 1930. The U.S. Congress passed the Tariff Act. It is also known as the Smoot-Hawley Act because it was promoted by Senator Reed Smoot and Representative Willis Hawley.

The law raised import tax limits for about 900 products by 40% to 60% in order to... [+]

My mother always says: “I never understood why World War I happened. It doesn't make any sense to him. He does not understand why the old European powers were involved in such barbarism and does not get into his head how they were persuaded to kill these young men from Europe,... [+]