The value of literature in the staging of peace

- We have referred to the topic of literature and memory. That is, the memory of the political conflict, reflected in fiction. We have started a round table from a number of premises. What do we talk about when we address the conflict? Here's a premise. And so have the words, because the issue is polyhedral, like the novels that reflect the Basque conflict. There is plenty of room for this. Some pointy and others incorporeal. The question “Can literature help overcome conflict?” has been the central axis of the conversation. But the question, in Tzvetan Tódorov, contains the following quote: “In societies where conflicts or civil wars have been experienced, literature can help overcome the situation, claiming universal rights. The appearance of dichotomies (e.g. through Manichaism) allows hatred to persist. Therefore, a mature culture can explain what has happened in this situation, but always from a human point of view”. We have been around the words “the human”, “the conflict” and “the trauma” it has generated.

Can literature help overcome the conflict?

Juanjo Olasgrip: If so-called compromised literature serves to change society, can literature help overcome conflict? In part, yes. That is, to the extent that it serves to reflect or symbolize reality, the literature may reflect or symbolize the conflict. However, policy [the politician] must overcome the conflict. And what I suspect – because we are in times of crisis or because we are as close as the end of ETA happened – is that this is not being asked of other people or entities. I have doubts as to whether they are asking literature for things that should be required of politics to represent peace or “trauma.” I mentioned the representation of trauma. That's the key, to me. I learned in South Africa that overcoming conflict, overcoming trauma, needs to be represented in part. In this representation, literature has a lot to say, but the solution is not literature, the solution to the problem is politics.

Iratxe Retolaza: Literature can, to a certain extent, be a propitious space to confront reality. That is, knowing the experiences of others and putting them in the place of others. Literature is a place for reflection. But for this reason, the literature is not enough, it is very important how the text is socialized, and at that moment the reflections and readings made in the socialization of the texts of Basque literature – many interpretations of literary texts – are made from the institutional and political parties logic. That's very dangerous. In other words, in the literary text we use the possibilities of breaking the possible dichotomies, the linguistic codes of the political sphere, etc. In this way, the possibilities offered by the literature to socialize the theme are broken. In a novel you have to appear as a member of ETA and therefore you have to be in favor or against ETA. There are many other issues in this novel. That is, the discourse of the political sphere comes to some extent to other relationships, other codes and dynamics that literature, and culture in general, can create.

Mikel Ayerbe. Perhaps ten years ago the question “Can literature help overcome the conflict?” was not raised. So, maybe he wondered, "I could help you understand." So does literature bring more than politics or journalism? Yes. The literature allows to deal with some themes, introducing into the game characters that do not match ideologically, and thus find characters or themes that you cannot imagine. It is a question of generating questions and drawing conclusions. On the positive days I agree with what Iban Zaldua says in the essay That weird and powerful language. That is, it helps, even in homeopathic doses. Then, it should be remembered that the social perspective on the conflict in the 1970s is not the same as the current one, nor the reflection of the conflict in the literature of the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s.

Tódorov says that “an adult culture can explain what happened in times of conflict, but always from a human point of view”.

I. Retolaza: In line with what Ayerbe said, we are at the end of a stage, but each one lives the conflict in a different way and the end lives differently. Speaking of Tódorov’s quote: I do not think we are about to reach a “pact”. Literature can help, but the communities within Basque literature, those involved in the conflict, are just a few. The influence of literature is scarce and also occurs in a single direction. Do you have a site as it comes back, but if it doesn't come back? For example, the novels about the 1936 war: Francoists and communists referred to a code that understood and affected each other in a literary system. Today, only the texts we create in the Basque literature affect a part of the communities in conflict.

J. Olasgrip: In other words, it does not affect a victim in Madrid. After the civil war, I'm talking now about memory, a new subject emerged. Francoism legitimized its origin through its literature. So somehow, it legitimized the way things were done because Franco won. This has not happened here, and it will not happen because one side has not exceeded the other. We seem to be in a state of impasse. We do not know how the political situation will be overcome. Will it be integrated into the status quo where there is a part of the conflict? I believe that a new political subject is not going to be created, it is going to get devoured. There is no consensus. I understand what you say [Retolaza], but if you only count on one side, others are not interested. Perhaps in our literature the victim of ETA, who has been escorted, rarely appears.

I. Retolaza: I do not agree with that.

M. Ayerbe: Times change. Today talking about ETA is much easier than it was fifteen years ago. The signal that's changing that appears in the literature. In the novels of the 1970s there appeared an ethical and moral justification for the involvement of a person in the armed struggle. On the contrary, as the literature has been developing, the field of victims has been changing. Since the 1990s, one of the themes is not the victim's, but the executioner's. Nor can we forget the written literature in Spanish, which has been more concerned – to the extent that it has been a gap in our own – with ETA’s militancy. The image of ETA has been caricarized more in Spanish books than in Basques.

I. Retolaza: How it happened. In the case of Jokin Muñoz, Bizia lon, there is a caricaturization of the ETA member.

J. Olasgrip: I don't think it's a caricaturisation. The conflict has created a traumatic subject that is described in part. Carlos (Atxaga's man in solitude) is a broken guy. In Muñoz Bizia's last story, in a way, it seems that realism is not enough to tell, so there is a mismatch, a relocation to tell the trauma. Barrutia, the protagonist of the novel T (I mean my novel and forgiveness) is like this. Another thing is whether they're good novels or not. What is Muñoz's character exaggerated? In that sense, conflict creates a crazy character. A note: Barrutia is not an ETA militant.

M. Ayerbe: This is an exception. The most cultivated in Basque literature is the transunto. How to tell the ETA militant, starting with Exkixu [Txillardegi Novel]. When I refer to Spanish literature, for example, through the character of El Lobo, I mean that Spanish approaches the art of consumption. I remembered them when I referred to caricaturization. On the one hand there is the unwise Basque, and on the other there is the one with very clear convictions. Basque writers seek their motivations. The ETA member is in doubt when it comes to making decisions. In the decision to enter ETA the protagonist of the son of the accordionist [Joseba of the novel of Atxaga] there is a point of madness, nobody knows why. That's in a lot of novels.

I. Retolaza: That is why, when talking about the Basque conflict, I wonder whether there is only talk of ETA members. That voice of ETA victim and ETA members often appears because there is a ghost. He's a collective character, a reflection of a community, with a point of insanity. Today the report of an evolution is shown (A. In the dust of the House of Lertxundi) and (I. In the mouthpiece of Borda) the characters are more human, but they are highly stigmatized, as if the community were homogeneous, as if that community were the Abertzale left. In Martutene [Saizarbitoria Novel] appears on many occasions. As if it were the position of a family, sometimes it seems to me that a collective character has been created to express that the left Abertzale too ETA. I wonder whether the Basque novels are made from the discourse of the political sphere. The crazy person suddenly appears, like it comes out of context, but it seems that that subject is not the one who decides.

M. Ayerbe: A justification is sought. In order to enter ETA, one has to count, in some way, the father's participation. The son of the accordionist does not tell when the ETA decision was taken. But compared to the son of the accordionist, in the path of the Ganso de Muñoz there is an evolution of the subject; also in Martutene. It shows Julia's evolution and then she moves away, there's a development.

I. Retolaza: But there are two possibilities: contempt or I admire it. In this dichotomy, in general, the posture is of the characters. The word "crazy" appears very often. One thing is how they are represented in the collective imaginary and another is the personal experience. One thing is the image and admiration of the madman, and another is the reproach, and in the midst of all the opposition of society.

J. Olasgrip: Until the 1990s, Basque literature has been characterized mainly by characters of nationalism, armed struggle and attacks. Then there's another evolution. That is to say, the view that only by writing in Basque does we have to be Basque. In the Basque literature there is a justification – or otherwise – for this, without completely rejecting this vision of the Abertzale world. Unconventional means are used to say that something is wrong. Then on the one hand it looks like a cartoonish character in their favor and vice versa.

M. Ayerbe: Major events are often used: “I entered ETA for this motivation.” I didn't find it in the house dust. Why he helped him. [Protagonists] She has admiration for her, but she's not a lover. He opposes the father, but there is no anger. So why? Because you could expect it to be done at that time? In Mea culpan, by Uxue Apaolaza, that side has become much more sincere to me. The testimonies of the conflict are more present than the participants. This causes a sense of guilt to the protagonist, which leads her to condemn. It makes a lot of reflections. The novel does not seem round, it lacks some hook, but the reflections are sincere. That is, to what extent is it possible to do it without essay, chronicle or autobiography? In a novel, these elements are difficult to reconcile.

I. Retolaza: The novel shows the feeling of guilt felt by the character. Many of the things that have been done in our literature have been done from the perspective of the 1980s, in our generation there has been no hegemonic thought, in our own, thought has been illegalized.

J. Olasgrip: No, Retolaza. I don't mean illegal or hegemonic thinking. If you write a novel in Euskera, in fact, I wanted to underline the brand that you are Abertzale. To get out of there you have to say, “I’m not that, I’m this.” From the 80s or 90s? That does not mean that it is that hegemonic thought on the street, but in the main cultural production there was talk in Basque – I dare not say that it is spoken, because it is then – that has partly limited what has been wanted to be said and how.

I. Retolaza: I have not lived the memory of the 80s like you [Olasgraberi], I have collected it in another way. I have lived it since Atxaga leaves, since it takes legitimacy. Ur Apalategi was asked in Galicia: “Therefore, to be a Basque writer and canonical, according to your speech, you have to be non-nationalist?” Answer: “Well, yes, that’s it.” The Galicians saw it very weird in the 1980s.

Let's keep talking about trauma. Can literature at least calm the trauma?

J. Olasgrip: The traumatic subject has appeared in the Basque literature for a long time. What does trauma mean? That you lived the situation, that that situation has suddenly broken and you are no longer subject. You've broken the conditions you had, you've got to go through a passage of that kind, and maybe you can create yourself as another subject. If you are a strong subject you will overcome all the above, but otherwise you will remain there, weak. That is what happens to the victims. Some characters are also left in the literature, it is a passage, they leave in a different way. I'm interested in this subject of trauma, both political and literary reading. In the political case, it seems that trauma has ended in a very traumatic way, that socially there is no cure. In South Africa every week the trauma was represented, there was a television series in which a special judgment was made in which everyone counted what they had done. In other words, this is not working here. For particular interests, for crisis, because there is no money.

M. Ayerbe: In this respect, I believe that what happened with the Twist novel is significant. Harkaitz Cano decides to make literature of a terrible event that lived in this town. He has used the Transuntos [Soto and Zeberio] to make the novel. This is not the case, for example, with the novel The Cold Blood by Truman Capote. Cano has made fiction. He says that he was not with the family of Lasa and Zabala, who did not receive his testimony. After doing the novel he was with a family member [included in the report of the Sunday of Berria supplement] and there has emerged a dynamic in the policy line. But in the novel, it's not just that theme. On the other hand, on the occasion of the novel Martutene, in the interview of El País Digital the Castellanoparlantes readers asked Ramón Saizarbitoria about this topic. I mean, there's a premise to talk about it. Dynamics have been created, several victims have come together and a new situation has been created around them. In the case of Lasa-Zabala, for example, it has caused these victims to be talked about.

J. Olasgrip: Twist is a novel that helps to mourn, heal and emerge that wound. I'm interested in asking what we've lost and how we've clung to what we've lost.

So you answer.

J. Olasgrip: We are very melancholy attached to the status of a nation. Literature recovers an object when it is lost. Freud says that there are two ways to recover them: one, don't miss it and put the object inside keeping you forever. The other is to cultivate grief, to cry. You've given the object for lost and you put the desire in search of something else. Politically, the left Abertzale has reached the end of the trauma, we're in the post-trauma era, but it doesn't know exactly where it is, it doesn't know how to advance. In this sense, the community should find a different way of making a novel, another way of telling the situation.

I. Retolaza: That is why I have doubts about so-called “literary autonomy”. We are in the field of literature, and although we know that tension is always generated in this autonomy and heteronomy, we all believe that literature has its own framework, with its thought and its own ways of reading. Twist is a novel that helps to make that way, but when it has made the way, when it has come out in public, I have been questioned from a literary point of view. I mean, I don't know if it's good for reading or texting the book, and if there was a symbolic capital exchange going on. At another time he was in favour of the victims. This fact from the literary sphere gives me doubts, because in that book other ends of some social facts appear, therefore, I do not know if they have been blurred. Many times I do not know to what extent it is appropriate to transgress the path of the community to move forward.

Is literature at the service of politics?

M. Ayerbe: There is a different use than putting it into service. If you ask people what Twist is, they'll tell you it's about Lasa-Zabala. Because he's been taught that. The novel Hamaika pauso [Saizarbitoriarena] does not occur to anyone who is the firing of Ángel Otegi. And it's also about that, but it's not a symbol of it. That's in Twist, but it's not just that. Now perhaps the time has come to talk about it. We have to talk about breaking taboos. In this case, the literature is taken as a starting point or some experiences are taken. To me, though, I came up with the following question: What do you have to do to deal with this book?

I. Retolaza: I wanted to come to that, in line with what Olasgrip said earlier, I question the confusion with some initiatives in the field of literary policy. There's tension going on.

J. Olasgrip: In the end, literature runs the risk of a horrible thing becoming too aesthetic and, to some extent, zero.

M. Ayerbe: There's a milestone. Did you come with me from Mikel Hernández Abaitua? novel. He made a choice. “I condemn violence, on the one hand or the other. And I will be demanding with the two,” he said. The novel ends with the murder of Yoyes. The novel was separate from my hands, the book I received very late. It didn’t come as fast as other books, there’s the “use” mentioned above. I wonder if he then lost his symbolic value. When I realized that there was this book, "Where have I been?", I wondered. That's what's happened to me many times because I was young. On the other hand, today, when Mikel Antza says about the conflict after his expulsion abroad [interview by Xabier Montoia in ARGIA]: “What I have written is self-fication, it’s me but it’s not me.” Well, I have a lot of doubts. It leaves out the story the most important that has to do with the struggle for the liberation of Euskal Herria abroad. It says that telling that through literature is a mistake. Before that we have to work a few stops. He says literature doesn't help tell what's happened. It contradicts itself. I cannot read the book as if the writer were not the protagonist. And he does that, he does literature. There is a great contradiction, when I read the interview and the book, I thought it “is a contradiction because that book begins in the present.” It starts when he's a prisoner, he's now flashback, back to a place and a time. If he had not started in the present, he would not find any problems. But it counts until the 90s, when he entered ETA, as if the protagonist hadn't gotten into ETA. He says he can't tell what's coming next. But go back, “I’m telling this but from now on I’m not telling it.” Wrong.

I. Retolaza: This is an important issue. When we talk about such issues, when we talk about our relationship with reality, we talk about the position of writing, what it has done, but we cannot rule out who the protagonist and the author is.

M. Ayerbe: Mikel Antza, a member of ETA, who has intervened in the conflict, like Yoyes, is not just anybody in the conflict. So, in the case of Antza, if you do self-training, if Antza is the protagonist, I cannot remember many things about Antza and others not. Then it is significant, when writers write about conflict, in most novels the protagonist is the writer: The son of the accordionist, Hamaika pauso, Lagun izoztua, Twist, Martutene, Hodei berdeak, Bizia lo, Mea falla, Koaderno gorria…

Why will it be?

M. Ayerbe: Because writers have taken on a social responsibility, they cannot escape reality. To do this, it has the Goenkale teleserie, the literature of escape or fantasy. The writer has to distance himself for a moment. As Olasgrip said, he praises the novel. He reports facts and reflections, unfolds plans through literature. Joseba Gabilondo states that reality cannot be reflected as such. It somehow creates a double discourse. Cano makes a possible representation of the reality of the twists, and then comes all the concerns that it may raise.

I. Retolaza: After all, the narration of memory is always in question. It is recognized that memory is constantly rewritten. The novel becomes a gadget to build memory.

“The memory of the past is of no use if it is used to build an incrusible wall between us and the evil one, only by identifying innocent heroes and innocent victims and putting criminals outside the borders of humanity,” explains Tódorov.

J. Olasgrip: Those heroes are no longer “people.” They left. In a novel that recounts the return of the fugitives, the protagonist should, necessarily, repent of this idea as deeply rooted as the Basque Country. It should look at that situation which has made it live melancholy, because the socio-political situation has changed.

I. Retolaza: Because it's not about getting them back.

J. Olasgrip: I refer to the case of a novel being written. The character should have that problem. Another thing is how you fight it. I mean, you've gone, you've gone through trauma, and in a way you've penetrated into what had created you a trauma: For years you have lived immersed in Euskal Herria and dreams. When you come back here, the environment has changed in part, because you've also changed in part, so the character faces that.

I. Retolaza: That people are not in that, they have never been. Among those fugitives there is everything. That trauma that you say I'm not personally sorry around me.

M. Ayerbe: There are many who are escaped, and for different reasons. The fugitive can be given one or the other connotation. What happens is that they feel part of that community, that we feel. So?

J. Olasgrip: I'm always talking about a hypothetical novel. Conflict is trauma because it doesn't let you normalize your being.

I. Retolaza: There are a thousand things that don't let us be normalized.

J. Olasgrip: It's the trauma that doesn't leave you in your evolution, the trauma breaks your living conditions, not economic, and it breaks you with the mental conditions of living. In the case of the ETA militant, let's say in the case of Mikel Anza, the need to flee is trauma. If we bring that person as a character to the novel, suppose that he spends fifteen years outside – or in jail – then that character should explain – contrast – the existence he has kept inside and what he is going to find now. The novel will be held in that clash.

I. Retolaza: I don't think there's any trauma to that overcoming conflict. Ten or twenty years ago, many people – I am referring to the trauma of personal subjects – are returning today to a community that did not leave now and then.

M. Ayerbe: According to Joseba Gabilondo, there are no more death threats, and that is what opens a new phase, there is much less fear of speaking and writing, of tackling taboos.

I. Retolaza: However, in part, you don't have the freedom to work on other speeches. Olasgrip mentioned hegemonic thinking: right now one thing is to say what you want and another is the social pressure that allows you to do it. I don't know if it's so easy to write about some things.

Through fiction you can say what you want. Or not?

I. Retolaza: This is the case of Terra sigillatan [Joxe novel Austin Arrieta]. It expresses the need for self-censorship of the writer. “I’d like to say what I feel, but I can’t. I want to talk, but I can't, about self-censorship." Here, politically, the first point is the rejection, the rejection of a form of violence. That is the reality. So it is the first premise of the discourse that we have to adopt a concrete violence in order to be able to talk about anything. That's what's in hegemonic thinking.

M. Ayerbe: But that's the writer's personal choice, whether or not you submit to self-censorship. Then there are social consequences that a person can live. For example, there was a time when you couldn't make a joke around the village, you couldn't use some fictional mechanisms, because it wasn't morally well seen, because you thought you laughed. The situation of society has a great deal of weight. However, it has been some time since ETA left the violence. Of course, the wound is still not closed.

I. Retolaza: If there are wounds that are not closed... Suppose you have spent 20 years visiting a prisoner in jail. What is trauma? I don't know if those who say they're experiencing trauma are living this way. There's a gap between pain and speech, perhaps not enough speech. Those people are not writers. Writers don't usually live that, they don't have the same worries. It can be as simple as that. There's a lot of trauma, and if I were to write, for example, about illegalization, there are still people who are about to judge. Terra sigillata is written at a particular time. The Euskaldunon Egunkaria newspaper is set around freedom of expression and freedom of expression in the Basque Country. There are many reflections, there is no complete self-censorship. I mean, he told it differently.

M. Ayerbe: So, back to the case of Antza: Why can't you use fiction? You can't write the names of people who are processed, but through fiction you can use some mechanisms to explore similar ways through invention. The literary initiative is a strategy, the writer is self-censoring or not. It says many things that are not expressed in any other way. Children's and youth literature is there. This literature expresses what many boys and girls cannot express differently, there is no other way. Pikolo by Patxi Zubizarreta. It tells the situation that we lived in when we were little. We say trauma, and maybe the situation is traumatic.

J. Olasgrip: I say trauma, because there have been deaths in the village. Situation not yet resolved.

M. Ayerbe: Yes. By the time we were born, the situation was already here.

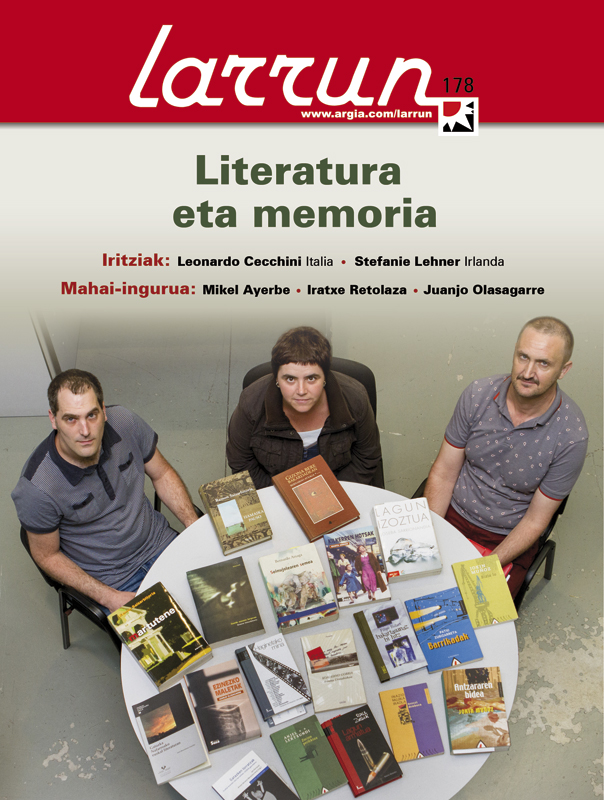

Juanjo Olasagarre Mendinueta. Hizkuntza Eskolako Euskara irakaslea eta idazlea.

(Arbizu, 1963). Psikologian lizenziatua. Literaturaren genero ugari landu ditu: nobela, poesia, antzerkia, kronika. Euskal gatazkari erreferentzia egiten dioten bi nobela idatzi ditu: Ezinezko maletak (Susa, 2004) eta T (Alberdania, 2008). Hego Afrikan egon zen aldi batez, eta Mandelaren Afrika kronika liburua (Susa, 1998) da haren lekuko. Idazlea. Volgako Batelariak blog literarioaren partaidea da. Euskal prentsan zutabegile da. Besteak beste, ARGIAn iraganean, Deian gaur egun. Hizkuntza Eskolako Euskara irakaslea.

Iratxe Retolaza Gutierrez. EHUko irakaslea eta literatur kritikaria.

(Donostia, 1977). Euskal Filologian lizentziaduna. EHUn eta USCn Doktorego ikasketak egiten dihardu literaturaren alorrean. EHUko Euskal Hizkuntza eta Komunikazioa saileko irakaslea da. 90eko hamarkadako narratiba: literatur kritika (Labayru, 2000), Malkoen mintzoa. Arantxa Urretabizkaia eta eleberrigintza (Utriusque Vasconiae, 2002) dira bere liburuak. Egungo euskal nobelaren historia (EHU, 2007) koordinatu du. Egunkari eta aldizkarietako kolaboratzaile, batik bat literatur kritikaren esparruan.

Mikel Ayerbe Sudupe. EHUko irakaslea eta literatur kritikaria.

(Azpeitia, 1980). Literatur Teorian eta Literatura Konparatuan (UB) eta Euskal Filologian (EHU) lizentziatua da eta egun, Gasteizko Letren Fakultatean dihardu euskal literaturako eskolak ematen. Gerra Zibilaren eta egungo gatazka sozio-politikoen inguruko ipuinak biltzen dituen Our Wars: Short Fiction on Basque Conflicts (CBS, 2012) apailatu du eta Euskal Narratiba Garaikidea: Katalogo bat (Etxepare Euskal Institutua, 2012) egilea ere bada. Berria egunkarian literatur kritikari lanak eginikoa da.

Now that everyone has become more Franciscan than the Pope, it’s worth remembering our unsurpassed classics. There was one in the 17th century, his grace was Arnaut Oienart. And since we can’t immerse ourselves in all his works, today we will praise O.ten youth in... [+]

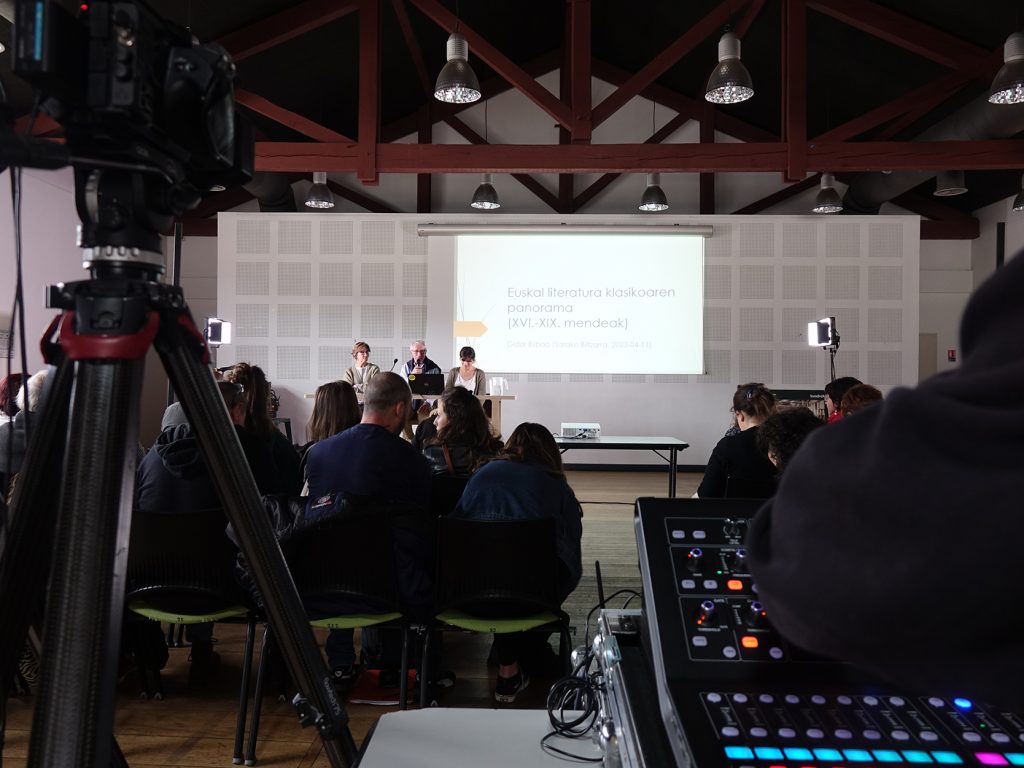

Aurreko tertuliako galderari erantzuteko beste modu bat izan zitekeen, akaso modu inplizituago batean, bigarren solasaldi honetako izenburua. Figura literarioaz gaindi, pertsonaia zalantzan jartzeko, edo, kontrara, pertsonaiaren testuingurua ulertzeko saiakera bat. Santi... [+]

Astelehen honetan hasita, astebetez, Jon Miranderen obra izango dute aztergai: besteren artean, Mirande nor zen argitzeaz eta errepasatzeaz gain, bere figurarekin zer egin hausnartuko dute, polemikoak baitira bere hainbat adierazpen eta testu.

Martxoaren 17an hasi eta hila bukatu bitartean, Literatura Plazara jaialdia egingo da Oiartzunen. Hirugarren urtez antolatu du egitasmoa 1545 argitaletxeak, bigarrenez bi asteko formatuan. "Literaturak plaza hartzea nahi dugu, partekatzen dugun zaletasuna ageri-agerian... [+]

1984an ‘Bizitza Nola Badoan’ lehen poema liburua (Maiatz) argitaratu zuenetik hainbat poema-liburu, narrazio eta eleberri argitaratu ditu Itxaro Borda idazleak. 2024an argitaratu zuen azken lana, ‘Itzalen tektonika’ (SUSA), eta egunero zutabea idazten du... [+]