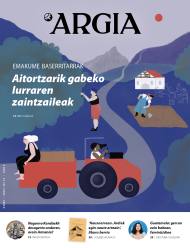

Peasant women, fundamental and forgotten

- If we had to imagine a farmer governing animals or guiding the tractor, we would surely imagine an adult man. However, the baserritars interviewed for this report have shown us that behind this folkloric imaginary there are countless ways of living in the field that are not recognized. They have reminded us that there are peasant women, who for years have supported the husbands and who have fed the citizens, but who have left them in the shadow of their husband, their son, their brother or the man in question. On 15 October, International Women’s Day is celebrated in rural areas, and they have stressed that, in addition to celebrations, they have to fight.

Although the situation has not changed, the steps taken in the rights of peasant women can be clearly seen, and one of the reasons is that in the 1990s, women in the primary sector began to penetrate and raise their voices. They exchanged what they lived in isolation and demanded together with the unions that they guarantee minimum rights. Until the 1990s, a woman could not request the shared ownership of the dwelling and in the year 2000, there were still barriers to being discharged from the Social Security system. “We have to bear in mind that the Equality Act was created in 2007, we are not talking about the time of Franco,” warns Alazne Intxauspe Elola (Andoain-Iurreta, 1984), EHNE Bizkaia and Etxaldeko Emakumeak.

But what does it mean to have shared ownership or to contribute to Social Security? “It provides personality and is essential for the acquisition of rights. Subsidies, the right to participate in institutions, etc. are linked to this,” explains Maite Aristegi Larrañaga (Bergara, 1962). He participated in the EHNE union at the beginning of the struggle for the fundamental rights of peasant women, remembering that they saw “very harsh situations”. For example, women who worked in the dwelling throughout their lives are without any rights. This was one of the main reasons to start organizing women in the household: “The law itself was very weak, clearly contrary to women’s rights, but implementation was also male in most cases, the obstacles were enormous.” Aristegi recalls the hardest cases, including women who were widowed or separated without any kind of protection and right.

.jpg)

Undeveloped laws

Aristegi acknowledges that the situation has improved a little, but Intxauspe looks critically at change. According to him, the law of ownership that was created in 2011 has not been developed at all, and both the household and the administrative staff have ignorance and lack of information. The Statute for Women Farmers (ERM), which affects the women of Araba, Bizkaia and Gipuzkoa, was unanimously adopted in 2015 by Parliament, thanks to the struggle of women farmers in recent years, but, as Intxauspe has pointed out, it has remained in the role, without success. The same idea is shared by Leire Milikua Larramendi (Abadiño, 1985) on the Earth, under the shadow of the Lisipe collection. Women farmers and book participation: “It’s a widespread feeling that there has been and is not interested in working, disseminating and disseminating ENE content.”

In the case of Lapurdi, Nafarroa Beherea and Zuberoa, their first status was in 1980, recognizing the women of the hacienda as “partner who participates in the work”. The equality of status of the partners they achieved in 2010 by creating the associative formula GAEC (Groupement agricole d'exploitation en commun). The organizers of Lurrama have revealed more significant data: peasant women had to wait until 2008 to obtain the same general maternity leave for workers. From 10 to 12 November, the Lurrama has been organized, under the motto "Peasant Women in Light", to recognize and recognize baserritarras women.

Widowed or distributed women were left without any protection and right

The acquisition of rights, shared ownership is subject to certain limitations, such as marriage or the actual partner. Intxauspe explains that no one has clarified whether shared ownership has advantages or not, and they are looking for new ways to avoid difficulties: “Here, most women have started building civil societies or using other simpler formulas.” Another problem that has existed in the issue of ownership is highlighted: sometimes the co-owner of a farm does not work or is not linked to the primary sector, but they use it to obtain subsidies, although women who actually work in the project are not the beneficiaries. Intxauspe stresses that many steps must be taken to develop and regulate the law: “There is not enough support to make these procedures possible, and for a 60-year-old woman it is not the easiest thing to do it telematically. This historical discrimination continues to exist.”

Therefore, older women are still the most disadvantaged and those who receive virtually no compensation for the work they have done for years. Because another drawback of the previous law was that it did not take into account the jobs women normally do, such as the transformation or sale of products. In the cited book, Milikua explains that the figure of peasant women is put in the shadow of men and as of the “family assistant”: “Through the figure of ‘Family help’, the invisibility of these women and their work has been formal and normalized”. What is more, if the person who takes care of the orchards and the animals is a man or a woman, whether they are married or not. By doing the same work, recognition is different. As Aristegi explained, this respect and recognition of women in the household is not exclusive to the Basque Country. He says that the situation is no better in Europe, as he has seen in meetings with representatives from various countries.

One of these meetings in Europe was the creation, in the 1990s, of the concept of food sovereignty by the international peasant coordinator Via Campesina, in which Aristegi participated as a representative of Basque citizenship. The idea of food sovereignty has become a key element for many baserritars and citizens today, and 16 October is used to recall this struggle every year. Intxauspe clarifies that this day is of vital importance for the women of Etxalde and exalts the work of Via Campesina, movement behind which he finds himself.

Auzolan not to overflow

To get to know the situation, we met in the Etxeita de Garai (Bizkaia) village with the women of Etxalde and a group of peasant women from Mozambique through Via Campesina. They call the auzolan in Etxeita: “This year there is a lot of apple and Anita, our partner, needs help making apple juice. Do you cheer?” they announce. Although it rains to the limit since the morning, the organizers say that the neighborhood work continues: “Let’s go slower, but let’s go.” Ana de la Maza Llaguno (Algorta-Garai, 1991) is a member of the Garai Conservak project launched four years ago and has for the first time in an auzolan, counting on previous occasions with the help of the closest to alleviate their obligations. However, in October last year the project overflowed: “I think it was because of the lack of support and recognition we have from the administrations, and because we alone fight with everything. Last year I overflowed, the work is not over, you have been working hard since May...” At that time he went to participate in the agrofeminist classes organized by EHNE, although with two children he found it difficult to find time, “it was worth it”. “The workshop moved me a lot. I felt support, it was a surveillance and dialogue room.”

Since then it has been tangled up with the Etxalde Women, and while looking indirectly to ensure that apple juice is not dropped to about ten neighbors, it confirms that the change has been huge. “It has been a huge force, fighting and reflecting together can be very nice. In most of the villages we have in Euskal Herria the model is familiar, and you go into your work and in the end you are alone, with those of always and with those of your sector. Once you messed up, you realize that we have almost the same problems, and you think about your project, but at the same time global.” So global that they have also come from Mozambique to learn about De la Maza’s project, and despite the fact that everything has accumulated on the same day and has not been able to arrive, it seems to him that there are very enriching initiatives such as the Nekazaritik nekazarora initiative, promoted by Via Campesina.

He emphasizes that Via Campesina is the only movement of this internationally organized size: “Now it seems that we are baserritarras the actors of old traditions and folklore, the frikis. But we're baserritars who cook, that's our job! We need food to survive, it's the base!" The women of Etxalde are clear about the model of this base: agroecological. “It will be for the primary sector in small and agroecological. That is, caring for society by caring for the land. It is said to be an infinite model, a process that always seeks improvements for land and for society.” Intxauspe has also joined De la Maza and criticized that administrations drive the industrial model, ignoring those who work in agroecology: “For us there are two money and they want us to settle. Consideration of the agricultural model is essential. Forget about synthetic meats and hydroponic tomatoes. Betting on a sustainable model and consensus on values,” he told the authorities.

When it comes to orchards and animals, whether male or female, it is considered either homemade or not. Doing the same job, recognition is different.

Both ensure that organizations do nothing but obstacles, and far from facilitating the work they do more laboriously: “I think we have been sending a clear message for some time, that is, we think we know where to go, but as Mixel Berhokoirigoin always said, the problem is not technical, the problem is political.” The need for profound changes has been put on the table, which would mean a change in society and in the system itself.

De la Maza has closely identified the changes in the agricultural model. In higher education, ten years ago he left the city to the countryside with the family of his partner who was born in the home: “I’ve seen how they were born from the agroecological model, now we give them the floor, but before it was a practice: to cultivate their mother both with wheat and with fruits and vegetables, and with some animal.” Remember that the agro-industrial model was promoted from Europe in the 1990s, and that those who worked in small and direct selling were treated as “poor, ignorant and unprofessional”.

Ana de la Maza: “In this house my struggle has been that I also use the tractor and that they lose their fear”

Now, when they tell De la Maza that she has to burn herbs with chemicals, “because it has always been done like this”, she asks them how her mother did, because “forever” that is more recent than she expected. He says that we must reconnect with grandmothers' modes, as the current industrial model is not viable. Yes, with more modern and electric tools to facilitate the process. As an example his model of farmhouse: “With the surpluses that are left today after the production of apple juice, my cows will be fed for a few days, and I will use the cow’s finger for the orchard; I don’t generate waste and I don’t provide fertilizer or I know where.” That's how the cycle goes.

Rural female caregivers

On the leap from town to town, De la Maza suffered the consequences of the masculinized sector, and says there are inequalities. From the beginning he began to do some work on the farm, but due to the gender roles, it was hard for him to accept the family that, for example, although he was a woman, could use the tractor. “In this house my struggle has been to get me to use this machinery and to lose the fear, because in their imaginary women are more dangerous in a tractor”. The incorporation of the feminist perspective into the primary sector is considered essential by women farmers organized and, on the contrary, the incorporation of the primary sector into the feminist movement. De la Maza clarifies an important point that is also detailed in the book Milikuak: “We are baserritarras, but also rural.” She denounces that, as a result of government policies, rural women are “very excluded from the cities”, exemplifying Garai: “Here we have no service, no public transportation, no doctors, shops, no child care services, we depend on cities.”

Intxauspe has asked institutions to make a feminist reading in rural areas and to put vigilance at the centre. In fact, the general feminist strike of November 30 will call for the revolution of the care system, and peasant women confirm that they have something to claim about care. De la Maza has criticized that rural women are required to be more involved in care and reproduction than urban women, as, among other things, car dependence and the need for more time to bring children. Likewise, he considers that further reflection on self-care and the determination of work and rest slots is pending, and it is clear that the path is to balance the distribution of care. “When I have to do a homework, do they say ‘what are you going to do with the children’? Children have a father!” According to Milikua, the fact that the responsibility for care rests with women prevents them from being present in decision-making centers or in meetings, that is, to promote participation men do not assume the responsibility of the family or the home.

That said, the main claim of women baserritarras will be on 30 November: “You cannot understand the care system without understanding the care of life: what we eat: seeds, land, animals... Without all this care you cannot survive,” Intxauspe summarizes. They stress that social surveillance is in the hands of peasants and De la Maza asks politicians to take responsibility: “He starts to take care of the primary sector, starts to wager on the agroecological model. They know that the industrial model is absolutely unworkable, but they don't go back."

During the feminist strike, they will seek time between the work of the house and the family to bring their demands to the streets. “Baserritarras women are very few, but we are here to say that if there is a change in the primary sector it will be the one that takes care of women,” says De la Maza. In their opinion, men continue to think about productivity parameters, and women are the ones who begin to become aware of global care.

Alazne Intxauspe: “You cannot understand the care system without understanding the care of life: the seeds, the earth, the animals… what we eat”

The peasant women of Mozambique have also left Garaia with ideas for the care of their peoples, announcing that “they have learned a great deal”: “We do not have apples, but tamarinds, oranges, sugar cane … but the one here serves us to make juices and jams”. A great deal of food is collected at some times of the year, but they point out that their main challenge is to bottle and pasteurize products so they can store all year round and fight hunger. In the neighborhood work, the peasants have left their mark. De la Maza has continued to bottle juice in the farmhouse, full of work but full of strength, moved by the greetings of the peasants of Mozambique saying “peasant force” and supported by the help of the women of the Auzolan.

"Isiltasuna oztopo eta elkartasuna lagun, egungo mundu gordina" kontatzeko erronkari lotu da Axut! antzerki konpainia.

Frantsesenia lizeoa, 70 urtez Ipar Euskal Herria barnealdeko laborarien formatzen.