"We were always looking at Mount Anbota to see if there was an airplane coming in fear"

- The Barreñas are victims of a long chain of repression that has not ceased for decades. Apart from the bombing, many knew about exile, war and prison. For example, a brother of Martin Barreña Elizegi and two of his uncles disappeared during the war.Martin was 9 years old on the day the bombing began, and he remembers with great horror what he lived there. Her daughter, Maite Barreña Oceja, and her grandson, Mar Agirrebengoa Barreñagaz, meet for the colloquium to reflect on the impact that this attack and the subsequent repression have had on the family. Home transmission is essential to keep the memory alive.

Martin, how do you remember March 31? What did you do at the start of the attack?

More places to stay in Martin: My father would get up at 7:00 every day and go to Izurtza, the pine forest near the cemetery. I stayed for breakfast and lunch. We started to hear sirens. Then, at the beginning of the bombing, we felt the bombs nearby. We lived in the alley, and one fell in front of Santa Susana, in the area where we lived. A tabike fell on us in the house, down the stairs. That’s why we couldn’t get down at first. We started asking for help, everything was taken away, and the landlord took us to the shelter. I was crying. Josephus, a friend of my mother, cleaned us out. Everything in the alley was dust, residue, column...

You went through that initial moment of the attack and went to a shelter.

More places to stay in Martin: An hour later, my mother arrived. Around 10:00 or 11:00, they took us to El Retelado, the refuge there. We left when the atmosphere relaxed. We saw Olea carrying her dead son in her arms towards the cemetery. The aircraft reappeared in the afternoon. They were hunting birds. People were machine-gunned, and we went into the ditches. They were very low, you could see the pilots. We were very scared. We were always looking at Amboto to see if there was an airplane coming in fear. The last time I saw them was when they went to bomb Guernica.

You were a child of war, too, weren't you? How did you escape from Durango?

More places to stay in Martin: In Bilbao, they put us on a boat and took us to Santander. There, we entered the Cuban ship called La Habana and went to France. They came to Bordeaux and took us to two houses of Jehovah’s Witnesses. We were there three hile.

Then it was time to go home and see the change...

More places to stay in Martin: In Irun, his mother was speaking in Basque and was put in prison. He was released accompanied by a so-called Satrustegi who had great power. They came to Durango, and they didn't give us any weight. We were welcomed into the home of a Karlista. There was a plaque that said, ‘Respect this house of the Carlists.’

Your father and brothers also suffered repression...

More places to stay in Martin: Brother Paco was in the labor battalions, then in jail, and left for 27 years. My father was also in jail. Brother Antonio, for 13 years, was alone when we were outside and was selling coal.

How did you deal with Freemasonry?

More places to stay in Martin: We went ahead selling pineapples and wood until my father started working. My mother knew Basque, but when she was arrested... there was fear. Durango didn’t speak much Basque because it was a Karlista camp.

On the other hand, you have a rather strange anecdote about cohabitation with adversaries.

More places to stay in Martin: A captain of the Civil Guard was our neighbor and we got along well. He would come to our house to watch TV; when the midnight part came, I would cut the signal and he knew why it was.

As a result of a strike developed while you were a worker, you were also imprisoned for some time.

More places to stay in Martin: There was a strike in Durango. Many were taken to the Civil Guard barracks. ‘Martin, if you surrender, the strike will end in Durango,’ one told me. I went to the police station and they told me I had an appointment for the next day. But the next day, the Civil Guard came and took me to Bilbao; I spent two days in La Salve. From there, to the prison, in Jaén. I was three hairs. I had a lot of fear. They took me out at night, put me in a car with the cops, and told me I was in a quarry eraman.Fusilatuko.

In love with: Can anyone think that we would have the labor rights we have today without the struggles they have fought for?

Dear, how have you received at home what your loved ones experienced during the bombing and the war?

In love with: The memory that I have since I was a child is that we were not the same as the others. I knew we were lost in the war, but I also knew that I belonged to a family that continued to fight for certain ideals. I have not lived in the form of hatred and revenge for the war. They continued to educate us in dignity within these ideals. We are the children of the workers; we are what we are for them. We have been educated in our commitment to the people. We have always been excluded; being Barreña in Durango was not neutral. However, our parents did not nurture our revenge; they have always been generous and hardworking.

In many cases of witnesses to the bombing, suffering has been carried in silence for trauma and fear. There seems to have been a break in Durango’s history that day.

In love with: I'd say there's been no interruption in our house. Despite losing the war and maintaining Francoism, for us it was not a closed process, we were still fighting. Mar’s mother made a political commitment to go to school; when Martin was arrested, Mar was three years old. I had to run with my dad during the demonstrations. We have always imagined the struggle as the only way to achieve freedom, because the only way to achieve dreams is through social and political commitment.

More places to stay in Martin: We have always been persecuted in Durango. One brother was an anarchist and was charged with the murder of the Durango sheriffs; the house was searched every 15 days.

You're from the third generation, Mar. How did you come up with the story?

To the sea: I have lived in a different way. I’ve heard stories many times, but it’s hard to live that moment. You can't imagine going through things like this not so many years ago. We all know that the story of Uncle Nicolas, who hasn't shown up, has been searched everywhere... What I heard from Dad: ‘If you have a son, let him be called Nicholas.’ The suffering you have endured has not been passed on to us. Now, when my parents tell me that when I was a kid, I was scared when they bombed, I'm really excited.

Does Aitite Martin tell you the story or did you ask?

To the sea: Dad likes to tell. If he has a memory at lunch, he tells it, and then questions arise, we have curiosity. “We went to war hungry!” my parents tell me if I don’t finish the meal.

For many years there has been very little talk of the bombing of Durango. In recent years, however, studies and tributes have been organized since the popular initiative. The City Council will now file a complaint against the authors. How do you see the process?

In love with: I believe that all the steps that are taken are important, but in Durango, progress is being made on some issues without closing the wounds. To close the wounds, it is necessary to tell all the truths and the truths. It requires a much stricter and deeper responsibility. This country needs truth, justice and reparation. There have been some in Durango who didn't give their father a job because they were Barreña. Some have gotten rich by stealing from us who were red. Like us, there have been many families in Durango. They owe us a debt linked to a historical truth.

Sea, what thoughts does the family transmission leave you looking forward to?

To the sea: My mother and my aunt are six children, and they all went to school. If they have made their living, it is because there is an effort behind them. If they did, why not us? It's a lesson for us.

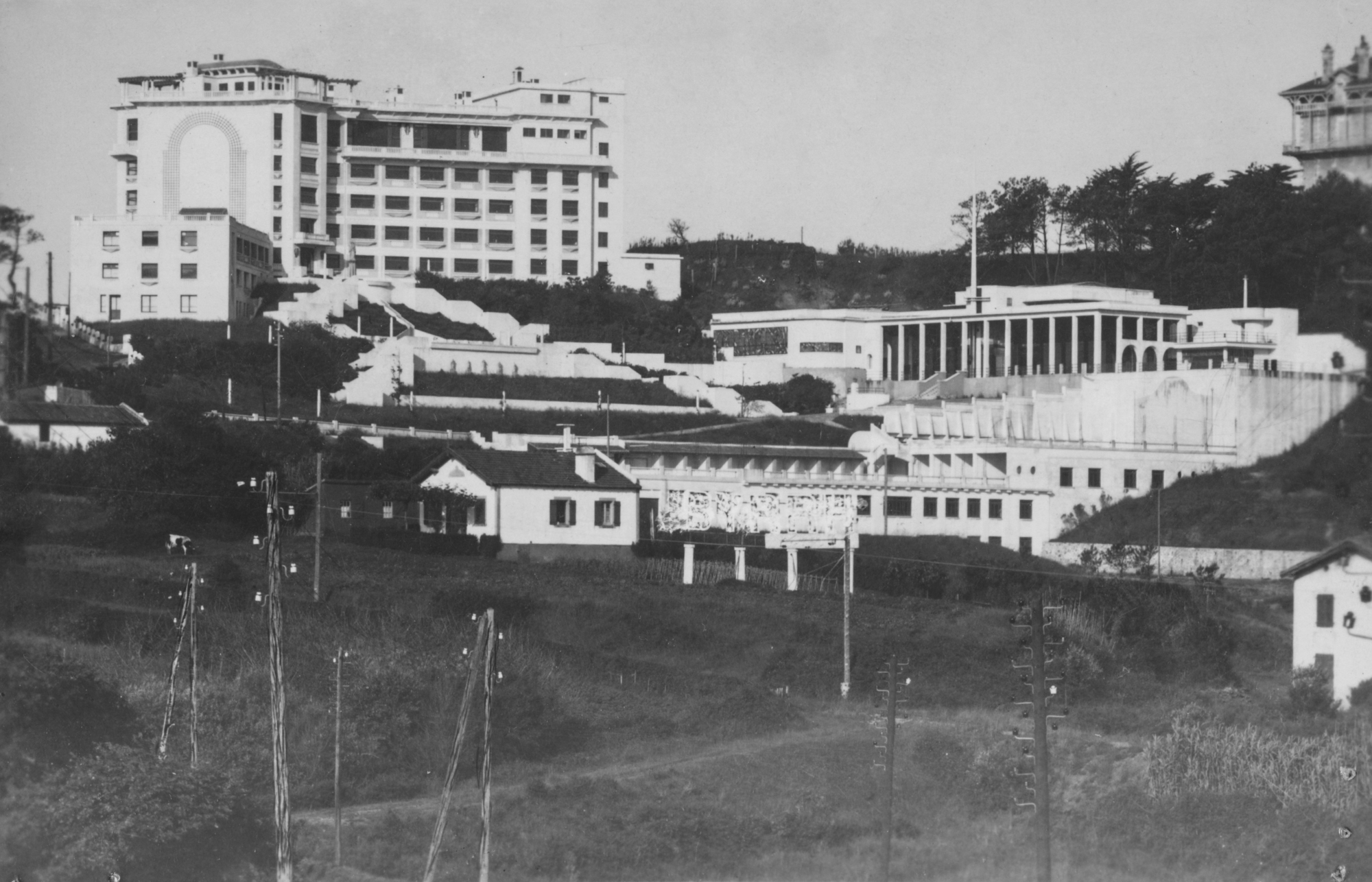

Nicolás Barreña, disappeared during the war, but not forgotten

The Durango Nicolás Barreña was a member of the anarchist battalion Malatesta during the Civil War. He was imprisoned and kept in the concentration camp of the Sardinero of Santander. There's no news of him since, he's disappeared. According to the latest information available to his peers, he left the concentration camp. But despite the search here and there, his relatives have not found any trace of him. “They were more likely to kill him, whether he was shot or on the run. Besides, we were told not only to hide the matter, but to leave for Russia! Her parents and siblings have died without knowing what happened,” explains Maite Barreña. They have a special memory of their uncle Nicolas at home. “My uncle’s presence has always existed. There was a truth that could not be told, but we had a witness to it. At home we have always had the flag and the Republican flag, we have always celebrated the 14th of April”, says the grandson of the disappeared person. When I was little, playing, my grandchildren dreamed that they were part of the Malatesta battalion. About the plate Nicolas is remembered on the plaque in the cemetery in honor of those killed in the war, but his relatives are not happy about it, says Maite. “Every dead person is followed by a story, it means suffering for everyone, but we have never understood how to put our uncle on the same plate with the fascists; it confuses things.” Martin continued along the same lines: “I didn’t like anything about the badge, and I’m sure my brother wouldn’t like it either.” Although it is difficult, they have not lost hope of clarification. “Let’s see if someday we can get more information about Nicolás, at least for his parents and to rest,” says Mar. |

This news has been published by Anbou and we have brought it to LUZ thanks to the CC-by-sa license.

Iazko uztailean, ARGIAren 2.880. zenbakiko orrialdeotan genuen Bego Ariznabarreta Orbea. Bere aitaren gudaritzaz ari zen, eta 1936ko Gerra Zibilean lagun egindako Aking Chan, Xangai brigadista txinatarraz ere mintzatu zitzaigun. Oraindik orain, berriz, Gasteizen hartu ditu... [+]

Gogora Institutuak 1936ko Gerrako biktimen inguruan egindako txostenean "erreketeak, falangistak, Kondor Legioko hegazkinlari alemaniar naziak eta faxista italiarrak" ageri direla salatu du Intxorta 1937 elkarteak, eta izen horiek kentzeko eskatu du. Maria Jesus San Jose... [+]

1936ko Gerran milaka haurrek Euskal Herria utzi behar izan zuten faxisten bonbetatik ihes egiteko. Frantzia, Katalunia, Belgika, Erresuma Batua, Sobietar Batasuna eta Amerikako herrialdeetara joandako horien historia jasotzeko zeregin erraldoiari ekin dio Intxorta 1937... [+]

Ezpatak, labanak, kaskoak, fusilak, pistolak, kanoiak, munizioak, lehergailuak, uniformeak, armadurak, ezkutuak, babesak, zaldunak, hegazkinak eta tankeak. Han eta hemen, bada jende klase bat historia militarrarekin liluratuta dagoena. Gehien-gehienak, historia-zaleak izaten... [+]

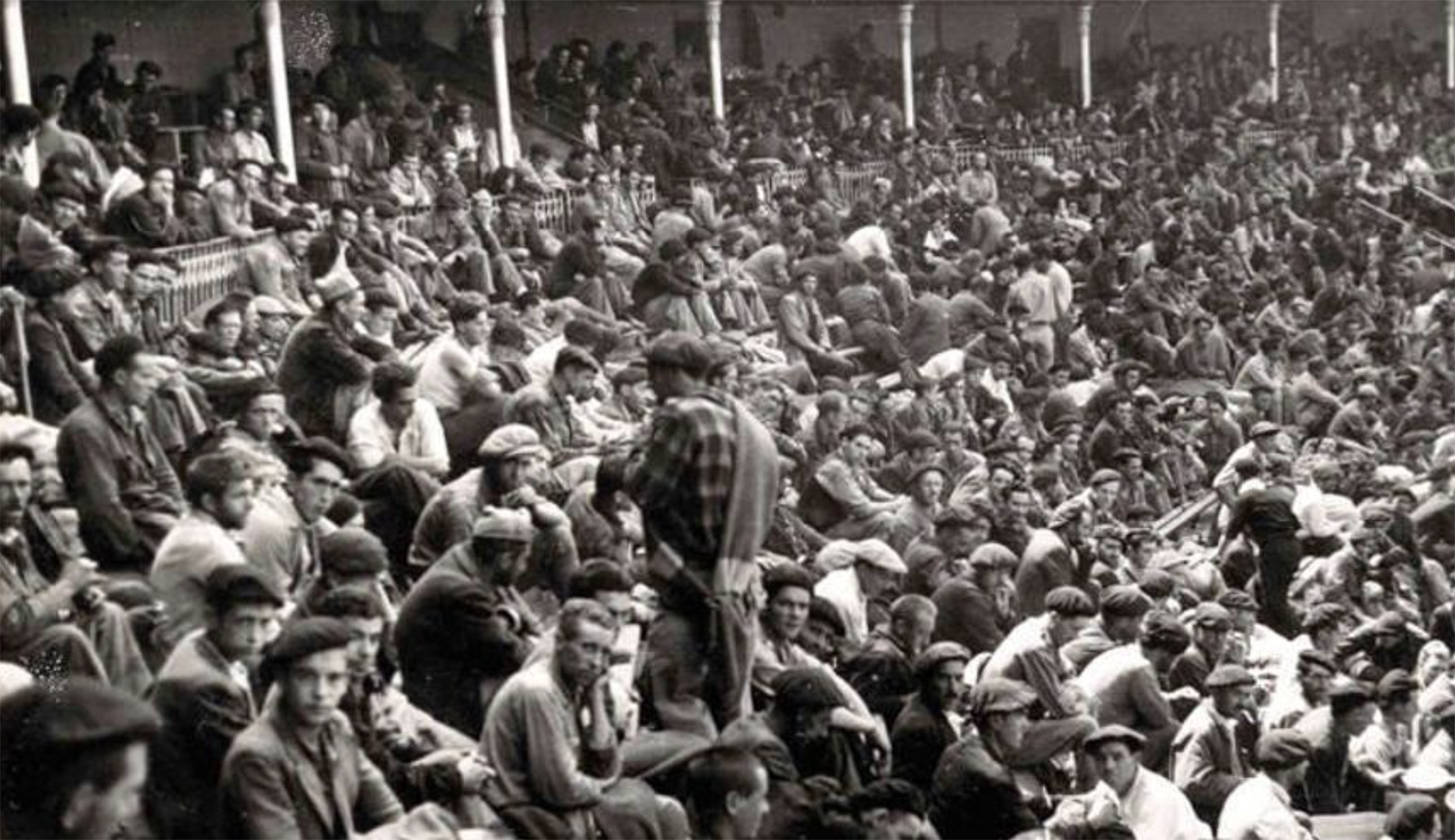

Pamplona, 1939. At the beginning of the year, the bullring in the city was used as a concentration camp by the Francoists. It was officially capable of 3,000 prisoners of war, at a time when there was no front in Navarre, so those locked up there should be regarded as prisoners... [+]