The ‘Egia model’ transformation map

From Egia, in Donostia, to Agurain, and taking in Amikuze, a new paradigm is opening up: ‘I want to live my life in Basque, you can answer me any way you want’. As simple as that. Bilingual conversations were the starting point for this new transformation. But to carry that out, some of the prejudices which affect Basque-speakers in terms of language have to be overcome. What we have to do is look at the map in the right way.

aurre egingo dieten hedabide independenteak

For me – I am going to write this text, which is also a confession, in the first person singular – a single piece of information was a discovery in itself. 80% of people in Hernani, which is where I live, understand Basque. To put it another way, we hear much more Spanish than we would like to in our industrial town, but only 20% of people do not understand Basque.

Our town's fourth “Eutsi Euskarari indar proba” ('Test of Strength for Basque'), called "Euskara Ari Du" ('It's Raining Basque'), follows in the wake of Egia's 2016 “Euskaraz Bizi Nahi Dut” ('I want to live my life in Basque') campaign, like the campaigns in Lasarte-Oria, Arrigorriaga, Agurain and Arrigorriaga, which Onintza Irureta describes in this number of ARGIA. The flyers given out in Hernani said: "Speak as much as you can in Basque. Can you live your life in Basque? Don't switch into Spanish. If you understand, don't ask me to speak in Spanish. Open your ears and try to understand". At the start of the campaign, a load of people trained for a sport they had never played before, and we have had a lot of different stimulating experiences since then.

I would say that the transformation is having bilingual conversations with people who do not speak Basque but do understand it. A lot of people who have decided to carry on wearing the 'It's Raining Basque' badge feel the same thing: "You carry on your way, I'm not asking you to change: it's me who's decided to change."

With the newspaper-seller, a 60-year old who speaks broken Spanish even though he long ago stopped speaking in Basque; in the bar you have your coffee, where, even though the air is full of Spanish, the civil servants, shopkeepers and retired people who are customers understand Basque perfectly well; who is it you cannot speak Basque with, if only 20% of the people in the town do not understand it?

"Would it be going too far to say that we, the people of Egia can make a difference by balancing things slightly back towards Basque, which is so much under attack, by reinforcing a strong urban district with many Basque speakers in it?"

Agurain's “Nik 75” campaign stirred us up: “In their language situation, is it possible to spend 75 hours in Basque in Agurain?” Well, it is: in Agurain 55% of people understand Basque! If I did not expect only as few as 20% not to understand Basque in Hernani, I would never have dreamed that 55% of people would understand it in Agurain, and who knows what sort of surprise I would get in Barakaldo… I was born in Aginaga, half-farmer, half-townsman, and there is no doubt that the way I have used language until now has been conditioned by a tenant-complex, as have the maps I have used to travel around the Basque Country.

I asked somebody at Aztiker Cooperative to help me because I needed new maps to take trips from my town, and the first question was: what percentage of people understand Basque in our towns? That is how these maps were drawn up.

The colour of Basque has changed

This map has become my main tool. The data has been taken from the Soziolinguistika Klusterra's latest Basque Database: people able to speak Basque, plus people who can understand it, in the Basque Autonomous Community in 2011; in Navarre in 2001 (updated in larger towns in 2011); and in the regions in the northern Basque Country in 2011 (information there is not available town-by-town).

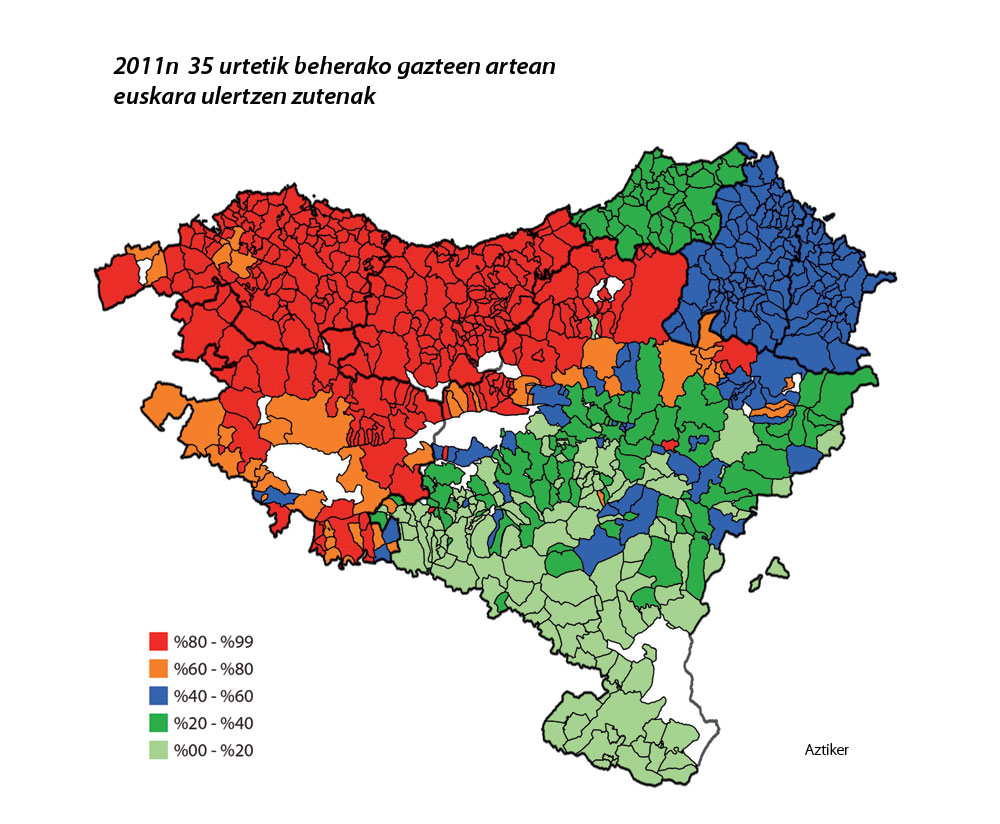

We have given each level of knowledge the same colours used on the last pages of Euskalzaindia’s 1979 Hizkuntza Borroka Euskal Herrian (‘Language Struggle in the Basque Country’) so that comparisons can be drawn: 80-100% in red; 60-80% in yellow-orange; 40-60% in blue; 20-40% in dark green; and 0-20% in light green.

What I have found is that more than 80% of people understand Basque almost throughout the whole of Gipuzkoa, with the exception of some larger towns (Eibar, Irun, Donostia, Errenteria…), in which less than 60% do. Most of Bizkaia is also red or yellow and, to my astonishment, Bilbao and the whole of the Left Bank are blue, with more than 40% understanding Basque. Araba delighted me: it is almost entirely blue (40-60%), including some towns in Errioxa!

Although Upper Navarre has clearly been overtaken by Araba in recent years, I was amazed by some towns (Iruñea and surroundings, Lizarra and Tafalla), where the 20% mark is surpassed. In the northern Basque Country, the whole of Zuberoa and Lower Navarre still go beyond the 60% mark, and, although we do not know about the situation in the non-Basque speaking towns (Maule, Donapaleu…), it seems reasonable to suppose that there, too, the 40% mark is passed. In Lapurdi, however, the situation is different: there is no comparison between towns such as Itsasu and Sara, and the Angelu-Miarritze-Baiona urban agglomeration, although the fact that 20-40% of people want to live in Basque gives us an idea.

This map will probably be questioned. For instance, how much do people who say that they "can understand" actually get? In general, however, looking at the Egia Model transformation map (you can see the towns in greater detail in the online version) has given me a lot more confidence about speaking in Basque, knowing the probabilities of hearing “No te endiendo nada” (Sp. 'I don't understand a word you've said') in each place.

Although this sociolinguistic information has been available for a long time, I am still wondering how I had not realised what the situation is long before now. I think I have had a mistaken idea about this all my life. The "Egia Model of the Basque Country" has amazed me, and given me a very different idea from the one I used to have. If this is possible, it must have been possible yesterday too… So what is the map I have been using until now? What is the mistaken map of the Basque Country which has conditioned me, a conscientious Basque language enthusiast, to use Spanish so much?

After speaking with a sociologist, and looking at other maps, my impression is that it was the map of how many people were able to speak Basque in 1996.

.jpg)

See the graph after this paragraph: That is what I have done over recent years, inadvertently calculating more or less how many people of my community there are in each place (in Lekeitio, Barakaldo, Orexa, Agoitze…), people who learned Basque as children, plus people who learned at school, plus people who learned at night school, plus militant new-speaker Basque enthusiasts… How could I get it right in Bilbao or Irun, not to say Donostia or Agurain?

We get older and Basque gets younger

But they have shown me a map about life in Egia which is even clearer, which makes me even more hopeful, and which you can see in next graph: Map of people under 35 who understand each other in Basque.

Look at the colour that the Basque Autonomous Community goes. It is almost entirely red! After looking at Graph 2, how could I possibly ask or answer a young person in Bizkaia, Araba or Gipuzkoa in Spanish? Zuberoa and Lower Navarre, despite the decline, are still blue, and Lapurdi and many towns in Upper Navarre are dark green (20-40%).

We will shortly find out how many people understand Basque in 2017, an advance of the new statistics being released in March. Seeing the real picture of the Basque Country according to the 2001 and 2011 data, what will happen if a few hundred people follow the Egia precursors' lead, and then thousands of Basques use the language during our daily lives?

"I would say that the transformation is having bilingual conversations with people who do not speak Basque but do understand it."

As the last Basque monolingual speakers who could have counterbalanced the Spanish monolingual speakers long disappeared – when our parents, who spoke in Basque with much greater ease than in Spanish passed away –, there are more and more people who find it easier to speak in Spanish, and, although they sent their children to schools where teaching is in Basque, they switch over to Spanish in their daily life.

Would it be going too far to say that we, the people of Egia can make a difference by balancing things slightly back towards Basque, which is so much under attack, by reinforcing a strong urban district with many Basque speakers in it? Or is that almost the only way to make clear to supposed Basque language enthusiasts of all political colours that we are condemned to live our lives in Spanish?

To tell the truth, I am talking more about my own interests as somebody who lives in Egia than about the future of the Basque language. I have realised that if I do not change my behaviour, I will spend my last years in the care of Spanish-speakers, just as our parents did. And I would like to live the last years of my life entirely in Basque. I've seen in Amikuze and Agurain that this can be achieved.

This article was translated by 11itzulpen; you can see the original in Basque here.