Artistic resistance in capricious constructions

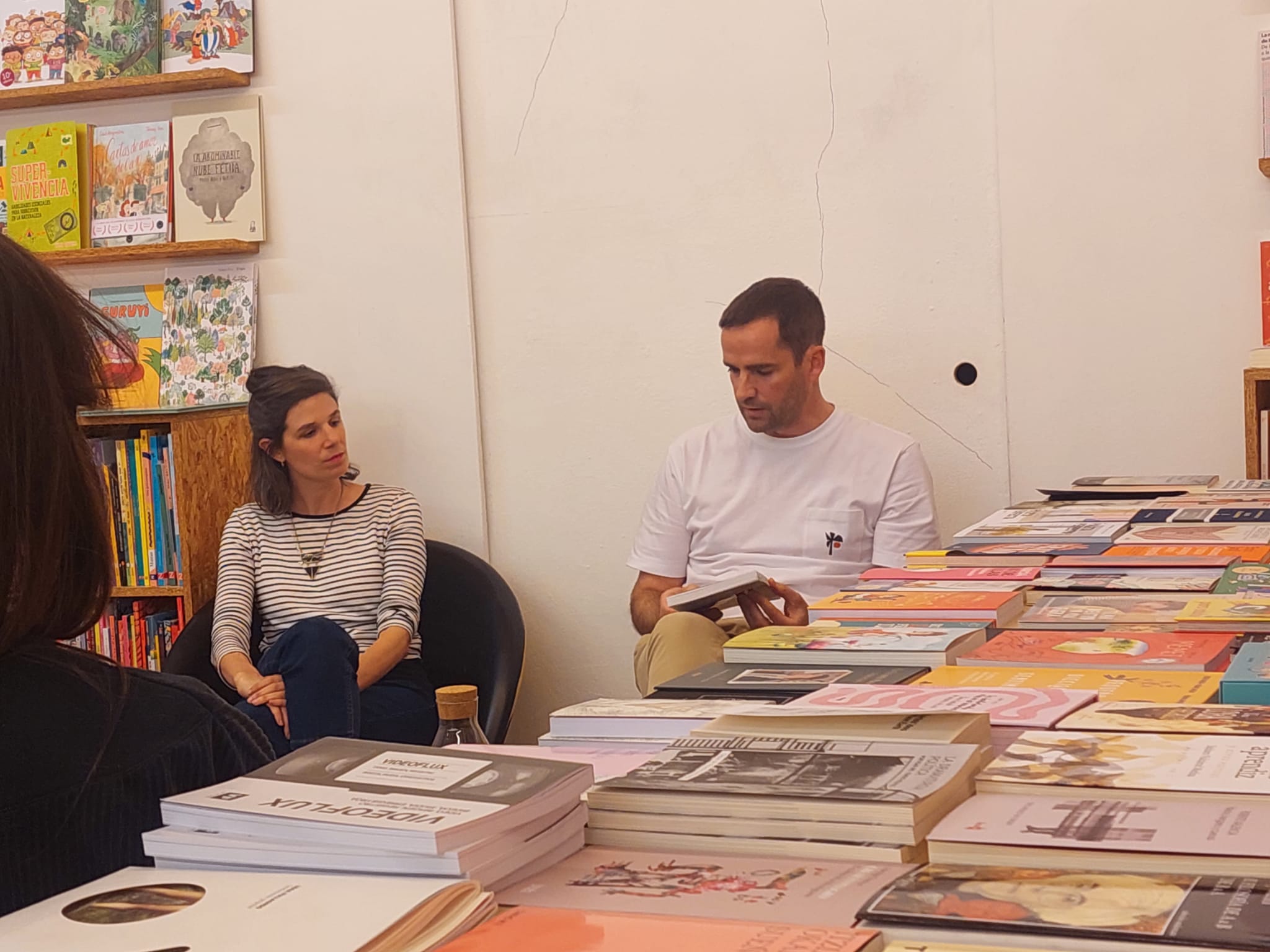

- Jone Alaitz Uriarte and Mikel Onandia will be in charge of learning what has been going on in recent years in the Basque art press. He will also know the rigorous looks that dissect artistic practices in his articles. And that is why he will be interested in the book Demontajes y ornamentos that emerges from the collaboration between the two: besides being a window to delve into the works of five contemporary Basque artists, they have offered numerous elements for an X-ray of our context, through their conversations with Sahatsa Jauregi, Oier Iruretagoiena, Damaris Pan, Daniel Llaria and Norea Aurrekoetina.

The protagonists of this book are of the same generation, all born in the 1980s and with a wide range of disciplines. For the authors, there are other elements that allow relating the works of these artists: “They share a training environment and a network of relationships and references that determine certain similarities, ways of doing and understanding art,” they explain in the introduction of the book. However, Uriarte and Onandia do not intend to present the quintet of the book as a representative of a generation. It is clear: “Our idea is not to give a closed canon.”

But having said that, the centers of interest and the production conditions of these five artists are also reflected in the trajectory of many others of the same generation, as explained by their authors. “In short, we are part of a system that largely conditions directly or indirectly the way of producing the art, as well as the way of showing and presenting the works, their format, their temporality…”, they explain. “We start from this overview to make a diagnosis or analysis of the system in which we live and at the same time participate, and then inquire into the singularity of these five artists, because each one has its own universe and is what really attracted us and has led us to make this book.”

The book that fills the gap

Demontages and ornaments is an object of book different from traditional publications, taking advantage of the freedom that the self-publishing of the work has given them. Each of the interviews has been equipped with a biography of the artist in which we will know the formation of each creator, the exhibitions made or their material working conditions, among others. In addition, photographs of some of the works of each have been interspersed to correctly locate the content of the interviews. They have printed a limited number of copies and each copy has a kind of belt with reproductions of the works of the interviewed artists.

“We understand the book as the back of an exhibition, as a support to develop the discursive dimension of artists”

Regarding the leading artists, they say: “They have been working continuously for years, and at this time, whether or not they are part of the market, their work is at an interesting level of visibility.” In other words, despite being young, they have already completed a journey to take into account, and precisely because of this, the fact of dedicating to their work in book format has allowed them to look with a broader perspective. “In an exhibition you can see art live, and that is the natural framework of art, but we understand a book or catalogue as the reflection of an exhibition, as a support for the development of the discursive dimension of art or artists,” explains Uriarte and Onandia.

On the other hand, it will also contribute to filling a gap: there are not many critical texts about artists appearing, not even about their generations in general. However, from now on, anyone who wants to analyze the ideas or work processes that underlie their artistic practice can depart from the base camp created by this work.

A concrete expression of postmodernity

Why bring these five artists together in one book? In addition to the time and context, how do they converge? For the authors, their works can be a sign of a concrete expression of postmodernity: the deconstruction of large narratives inherited from previous generations, the pessimistic view towards utopias, the review of many naturalized artistic aspects... All of them have not come from the hand of the artists who speak in Demontages and ornaments: “In the Basque Country in the 1980s, since Oteiza and post-minimalism, new forms of sculpture were defined and new references appeared, such as New York City,” explains Uriarte and Onandia. “The following artists have followed these paths by dismantling political, gender or artistic conventions. We would say that we continue in this paradigm, but the plurality in the definition of postmodernities, the recovery of different languages and ways of working and the hybridization of different raw materials and/or techniques, both in the trajectory of an artist and in a concrete work, have been generalized or expanded to become the main characteristic of current practices”.

To put it another way: “The Basque artists of 1960 and 1970 had a political conception of art, the creation of a language that defined their own identity in the national construction and linked tradition and vanguard. For their part, some artists started in the 1980s and 1990s, in a different context, addressed the political situation, in conflict, with a critical distance, focusing on identity codes and decontextualizing them. The young generations today have begun to work as references in their works, but postural violence has become a reality”, the authors point out. In the predominant chain of deconstruction in the last 40 years, the generation of Jauregi, Iruretagoiena, Pan, Llaria and Aurrekoetxea has made particular contributions: “Probably due to the existence of new times, other aspects have been added such as the centrality of the concept camp or the revision of the traditional relationship between form and ornament”.

In any case, these are not characteristics shared by all the artists of the book at the same level either, since, according to Uriarte and Onandia, if there is a current trend, that is the plurality: the coexistence between multiple proposals. In the works of Jauregi and Llaria, the demand for camp and kitsch is noticeable. Regarding the idea of ornament, it appears prominently in the works of Aurrekoetxea, when it brings to the foreground “the superficial, the ornament that does not affect the structure, the form of whim”: “This form is transformed into structure, as it does with braids. The form that is used in itself to collect hair becomes a structure if it is dense well.”

The importance of the process, through the tension reading with the academy of the interviews

of the Book, is another common characteristic that all artists call attention in their explanations: they try to work independently of closed methodologies and the tendency to excessive planning of the works. They decide the final outcome throughout the process, rather than from a fixed idea or an initial draft. “Those who happen in this process, whether they are mistakes or unexpected encounters, will lead them to the end, and that honesty that is there is interesting to us,” said Uriarte and Onandia.

.jpg)

It is not, again, a feature that only defines these artists, but in any case it serves to put a question on the table: How does the way of understanding creativity, to put it another way, combine with regulated art studies? As Uriarte and Onandia have pointed out, since the definition of modernity in the late nineteenth century, the conflictive relations between artists and academia can be observed. But the situation also has its paradoxes: “In recent decades, modern and avant-garde forms have been assimilated by the system, and in post-modernity, paradoxically, institutions and academia have assumed this language to become standard. In other words, today facilities, new technologies and formally avant-garde languages are academics. That's what you teach in college. So art and artists are always in tension with academia. The lack of methods, the centralization of the process, experimentation, are central to the practices of contemporary artists and the transmission of these forms of work is at stake”, according to the authors of the book.

Having said that, in the book it is clear that the Faculty of Fine Arts of the UPV plays an important role in the Basque artistic system. “The vast majority of artists in recent decades have gone through it, but the other institutions that make up it – Arteleku (1988-2014), Kalostra (2016), Jai (2020-2023) – or the stays of artists abroad (whether Erasmus or international residences) are fundamental,” according to Uriarte and Onandia. “Knowing the different ways of teaching is important because it is not a single way. And above all, artists work with artists.”

Art, from the spaces of formation of the Artists as spaces of resistance, and taking into account the trajectories of the protagonists of the Demontajes y

Ornamentos, can also be distilled some characteristics and deficiencies of the Basque panorama through the reading of the book. Among others, the disproportion between the number of artists and the police officers, mentioned in the interview with Oier Iruretagoiena. However, the assessment that most people make of the Basque area is not particularly pessimistic, but the limits of the current system seem to have been highlighted.

“Today’s young artists already live in a post-violence reality”

“It’s a matter,” explains Uriarte and Onandia, “that from a moment, especially after the age of 35, most artists have trouble making the leap to total professionalization. The private collector is very low and there seems to be an imbalance in aid. In this sense, it is a kind of funnel in reality from a certain age. In addition, we are a small town and the circuit runs out quickly. So, and this is not bad in itself, artists have to leave. It's about seeing if they have a chance to come back and stay, after being out or working. International networks may need to be strengthened.”

They have also looked in other directions: the figure of the art critic has almost disappeared, with the loss of space in the press, while figures related to education and programming have been imposed “probably by the evolution of the system itself”, according to the authors. Options that could be explored further at this time are also mentioned: “One path may be to bring external commissioners here – which is done in part, but perhaps not enough – or to get the commissioners out here.”

Despite the shortcomings, Uriarte and Onandia believe that art remains a “focus of resistance” in our country. Asked about this idea of the preamble, the authors explain that artists' attitude to the market may indicate this trend of resistance: Remember the case of Damaris Pan, for example. “He has worked for years, non-stop, virtually unexposed in the galleries, and now has achieved visibility and a place in the market, but not because he has searched for it, but because it has happened to him.” Obviously, it is not the only bet of this kind that appears in the book. “Dani Llaría speaks in his interview that she looks comfortable in that eternal amateur condition, herself, with just pressures, in the practice of art, experiencing, trying and learning and there is some resistance there”.

Last week, during the blackout, seeing ourselves vulnerable, we began to investigate many people in order to understand what happened: how does the infrastructure that transports electricity work? Why is it getting old? I am fascinated by the physical phenomenon of electricity... [+]

Eskultura grekoerromatarrek bere garaian zuten itxurak ez du zerikusirik gaurkoarekin. Erabilitako materiala ez zuten bistan uzten. Orain badakigu kolore biziz margotzen zituztela eta jantziak eta apaingarriak ere eransten zizkietela. Bada, Cecilie Brøns Harvard... [+]

Behin batean, gazterik, gidoi nagusia betetzea egokitu zitzaion. Elbira Zipitriaren ikasle izanak, ikastolen mugimendu berriarekin bat egin zuen. Irakasle izan zen artisau baino lehen. Gero, eskulturgile. Egun, musika jotzen du, bere gogoz eta bere buruarentzat. Eta beti, eta 35... [+]

This text comes two years later, but the calamities of drunks are like this. A surprising surprise happened in San Fermín Txikito: I met Maite Ciganda Azcarate, an art restorer and friend of a friend. That night he told me that he had been arranging two figures that could be... [+]

On Monday afternoon, I had already planned two documentaries carried out in the Basque Country. I am not particularly fond of documentaries, but Zinemaldia is often a good opportunity to set aside habits and traditions. I decided on the Pello Gutierrez Peñalba Replica a week... [+]