Heavy account

- The term phobia is becoming increasingly known, but what exactly is it and what is its magnitude? Trending, the most convincing definition says: it is the oppression that pushes obese people into situations of disadvantage, injustice and marginalization, which reproduces systematically and has a structural character. In other words, we are talking about the oppression present in daily life and in all areas. And healthcare is no exception. Even as a result of the link with health and lack of health, receiving coarse care in the name of health is not uncommon. Collateral damage is serious, as inadequate care carries a health risk. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the stigma of obesity can affect the quality of health care, affecting the health of this public sector and increasing the risk of mortality.

Studies like Gordophobia seriously impairs health, published by Marta Plaza in Pikara Magazine, are very illustrative. 12.1% of the nurses consulted for the study Attitudes of Nurses Toward Obesity and Obese Patients preferred not to touch obese patients. Another significant fact is the work published in 1989: 24.3% coincided with the statement “in general, the care of obese people bothers me”. Despite spending a decade, the study Weighing the care: physicians’ reactions to the size of a patient (Pisando la cuiaba: reactions of professional physicians according to the size of their patients), dated 2001, reveals a similar reality. The follow-up of patients who complained of migraines resulted in an obvious trend: as the patient's body mass index (BMI) increased, doctors showed less willingness and patience in care. It can be considered as a consequence of the moral judgment, since the greater the weight of the patients they were considered less capacity for care, self-discipline and health.

The situation has not changed much, as today obese people continue to suffer discrimination in health. Although I did not remember the literal words, a doctor of the same generation made me the following comment, when I had just worked: “When older women come to me for consultation, their flesh with madness, and to perform the auscultation I have to touch the chickens… what disgust”. Although it is a point comment, it can be read as an expression of the thickness present in health, in this case mixed with addiction and misogynist. According to the report published by the WHO in 2017, Weight bias and obesity stigma: statutations for the WHO European Region, 69% of obese people have suffered discriminatory treatment by physicians. There is nothing else to start asking obese people nearby to accumulate stories of people who for any reason have come to the doctor and have come home with a diet to lose weight. “In these cases the health service is really concerned about our health? Is it necessary to chase the size?” says the thick activist Magdalena Piñeyro in her book Stop gordophobia. The question is rhetoric, as indicated by its location in the book: it can be read in the Health Discrimination subsection of the chapter Common Places of Lodiphobia. To put the issue, Piñeyro talks about the last time he was in the medical office: he left with knee pain, injured on the mountain and the doctor responded that “we must stop eating burgers.” “I don’t like burgers, but that doesn’t matter (…) Because a fat person has crossed the door, and although it can come for a flu or because he has hit his finger against the mesanocho, the recommendation or the indirect comment will be: lose weight.”

Health: more than weight, related to art

Piñeyro is one of the founders of the virtual platform Stop Gordophobia and, although it has been closed this year, he has dedicated himself to collecting testimonies of the gruesome treatment suffered during his years of operation, among others. If we start exploring, most of them are anonymous. The woman who took her cousin to the doctor, for example: “When we were in the consultation she looked at me and said: ‘With no intention of disturbing him, but do you know how he should eat?’ (…) I told him as kind as possible: ‘Yes, the nutritionist has given me the explanations, with the indications of the gynecologist, because I have polystic ovaries’ [the syndrome that can cause weight gain]. ‘Yes, but that’s because it’s fat,’ she replied. Despite not indicating any kind of pain, although someone else should be cared for, this doctor patinized the thick body as if he had crossed the door of the health center sinuously. And this is because obesity is related to poor health. The Collective Manifesto of the World Day against Gordophobia (Collective Manifesto of the International Day against Gordophobia) reveals that “there are a number of factors that condition health and most do not depend on us and cannot be measured with simplistic parameters, and less with a scale. There are obese people who are healthy and can get sick, just as there are lean people who are healthy and can get sick. Health is not static or aesthetic, although BMI says otherwise.” According to the WHO, obesity is not a disease in itself, although it can be a risk factor for the development of diseases.

In consultations, it is frequent to attribute any health problem to the weight without performing diagnostic tests or questioning excessively and, consequently, tend to the underdiagnosis in obese people.

Actually, another is the most common health problem that comes from obesity and is related to prejudices about thick bodies instead of weight. In fact, the belief that obesity and disease go hand in hand makes it frequent to attribute any health problem to weight in consultations without diagnostic tests or excessive examinations and, consequently, a tendency to underdiagnosis in obese people. This makes it difficult to identify diseases or health problems, and is usually accompanied by another factor of lack of diagnosis: for not suffering any more unpleasant comments due to their obesity and humiliations, and for not hearing that the cause of the discomfort is their weight, since many obese people opt to let themselves go to the doctor.

The result of all the above is not a small thing: firstly, the health care of obese people is conditioned and deteriorated, which implies jeopardizing their well-being or worsening their health to a point that can be extreme. The side effects of the presence of thichobia in the health system can compromise life, as is the case of the 29-year-old American Amanda Lee, who came to the consultation saying that eating months ago caused abdominal pain and the doctor responded that maybe it was not so bad what she was told. In Lee’s words, blinded by the thickness, the doctor did not consider the “symptoms of colon cancer manual”. After receiving a diagnosis from another doctor, he uses his testimony to warn of the severity of the problem and report it. It is clear that “the voice in medicine literally kills”.

To illustrate the extent to which body size can condition the consultation, it is clarifying what Nathy of Valencia tells in Pikara Magazine's report: the fact that the COVID-19 thread replaced face-to-face care by the telephone allowed him to know that the discomfort he felt for years corresponds to lactose intolerance. “Since the doctor doesn’t see my face and my body, he has sent me to do more tests than those done all his life. The reason for everything that happened to me when the consultations were in person was weight. Now, because the attention is on the phone, she doesn't see that I'm fat, and she sends me to run tests, and if there's nothing clear, she asks to do more." Until they got it right. It was not, as was suggested for years, a matter of weight.

Alba Campmany knows well what it is to leave the consultation always with the same message. He explains that he has spent his whole life listening to the problem being his weight. After talking about his 28 years of painful health experiences, he leaves: “I hate going to the doctor.” It does not speak of frivolity because, knowing that it endangers his health, he has decided not to go through the door of some consultations. In 2019 he was diagnosed with polycystic ovary syndrome, so the pair of experiences he had in that sense encouraged him to make that choice. In the blood tests he was diagnosed with, a high level of glucose was detected, and when prescribing one medication or another, the doctor did not lose sight of the goal of losing weight: “Textually told me that not only with glucose, but that it helped me lose weight.” “It doesn’t matter if one of the side effects of this medication is the diarrhea that leaves me unable to leave the house, because if you lose weight it doesn’t matter the rest,” he ironically says. Since then he has not seen the doctor again by decision. Know the damage this can cause: “I have medical friends, gynecologists, everyone. And I've been told he cares about my decisions, because without medical follow-up, I can develop insulin or diabetes resistance."

He has also stopped going to the endocrine, a very hostile environment. He was there lately crying from the consultation and until today. The polycystic ovary syndrome occurred recently in the diagnosis, since it was submitted to diet, since feeding is usually one of the axes of the treatment. “I went to the endocrine without losing weight, even gaining some weight. And he told me it was enough, that I had to make a will.” He answered that he was doing what he could and that he went down.

Comprehensive perspective for a vision beyond the body

The diagnosis of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome marked a milestone in the life of Campmany, a second diagnosis that led him to become aware and reflect on his position as a thick person before health care. The diet is usually one of the axes of the treatment for polycystic ovary syndrome, and once the diagnosis is received, aware that weight loss would become central in his daily routine, he shared with the doctor with concern the idea that his relationship with food was not healthy and had certain dysfunctional tendencies with feeding. She went to the mental health area, where she received the second diagnosis: eating behavior disorder. “As a result of that diagnosis there was a chip change inside me and I started questioning some issues,” he says. Every time he had to go to the office, the doctor was more concerned about the prescription of the diet, although he knew he has an eating disorder. Thus, it began to question certain attitudes and to become aware of the obesity suffered, which led to the decision not to restart some consultations, as well as to deepen and investigate the subject. Social worker who teaches workshops on obesity and eating disorders. “If Alba five years ago saw me today, I would not have believed.”

Knowing that he had an eating disorder, despite having understood the suffering of the years, they offered him the key to questioning several issues, it did not mean any artistic improvement. Even in the consultations of psychologists and psychiatrists, the bulk prevented him from receiving adequate care. “It was as if the psychologist didn’t consider my eating disorder valid, as if because I was fat I wasn’t going to fit in that category (…) I was told it was a food addiction, rather than an eating disorder. I would say that this is a stereotyped imaginary, as if obese people ate up for pleasure.” He had a diagnosis, but he felt that they did not fully allow it in the area of mental health, and says that he had difficulty accepting the diagnosis as a result of the reception of this type of contradictory messages by the experts. Once identified a consultation that would not step again, finds a place to treat eating disorder in an association outside the public health service.

Campmany does not talk about frivolity when he says he hates a visit to the doctor when, knowing that he is endangering his health, he decides not to go through the door of some consultations.

A year and a half ago, the desire to have a child made him return to the doctor, the obstetrics and gynecology department. He was mentalized because he knew that weight control was going to be rigorous. “It is known that [in this field] this aspect is usually very heavy,” he says. To her surprise and joy was the first nice consultation with the midwife. She reported the eating disorder and asked her to climb to the back scale so as not to know how many kilos she had. The midwife did not block her, on the contrary, “it was very comprehensive, and she told me that she was going to include a note in the file so that those who attended me the previous moment would take it into account and not take the issue of weight back and forth.” However, women have found no more on the road and have since stated that the process has been “quite terrorist”. The details of the last visit are painfully reported: if it were not for his BMI, he was told that he would be a candidate for assisted reproduction. “From a BMI Osakidetza does not assume assisted reproduction, as the chances of success are reduced,” he explains. Although she has not investigated whether this is the case, Campmany believes that her problems getting pregnant do not correspond to her weight, but to something else. “That’s why I’ve asked for help, but I’m being denied that help because I’m fat.”

It lacks an art with integral vision, able to analyze people as a whole and complexity. He believes that, dazzled by obesity, many of the professionals who have gone past him have seen nothing but a eating disorder, nor other factors that may hinder pregnancy. Above all, he has given some brushes of the pain that this treatment produces: rejection of his body, feeling of guilt for being fat… are signs of the collateral damage at the psychological level of gross discrimination, which also produces loss of self-esteem and shame or hatred towards oneself.

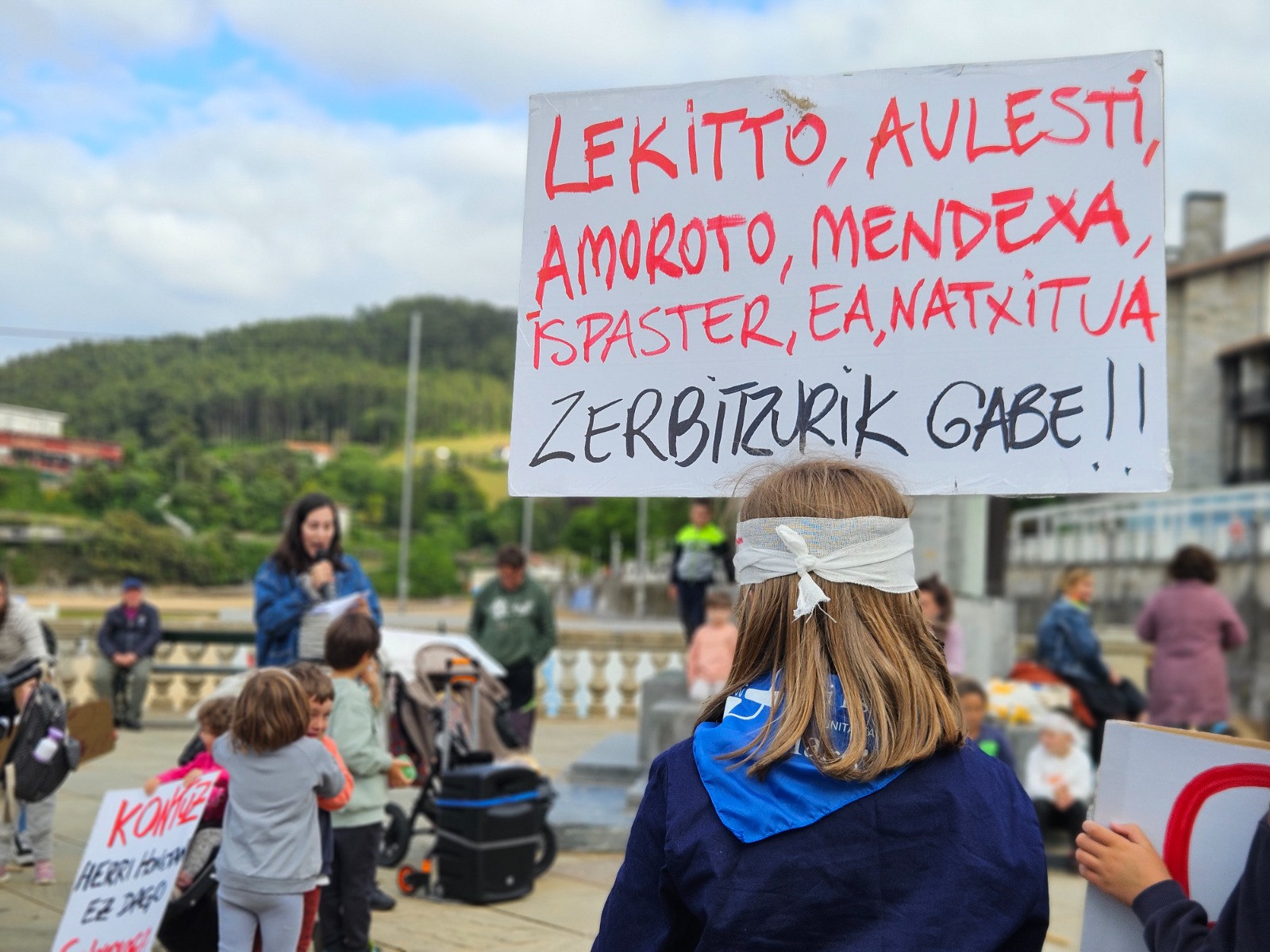

Campmany seems to have taken some steps: “Despite being a very small minority, I have found professionals who were more aware of this issue.” However, he wished to stress that there is much to be done and to demand comprehensive attention and unscrupulous perspective. In this sense, Piñeyro stressed the need to report the problem at the I Days of Thica of the Basque Country that took place in September: “It is very important to leave the consultation of a gordobo doctor so that the complaint is recorded later because if nothing seems to happen”.

Until her final stage, the linguist Carmen Junyent claimed the possibility of dying in Catalan. When she died, she wrote her experiences with the health staff and asked to be published after her death. In this way, he wanted to emphasize that language is part of the treatment of... [+]

Two years ago, the Catalan archaeologist Edgard Camarós, two human skulls and Cancer? He found a motif card inside a cardboard box at Cambridge University. Skulls were coming from Giga, from Egypt, and he recently published in the journal Frontiers in Medicine, his team has... [+]