Society

Environment

Politics

Economy

Culture

Basque language

Feminism

Education

International

Opinion

wednesday 21 may 2025

Automatically translated from Basque, translation may contain errors. More information here.

Lugares comunes, idées reçues

- The French and Spanish have a different way of naming it “cliché” or “topical”. Lugar común, a common place, is the expression that can be used in Spanish to express this concept, and in its liver we can perceive the community. Because all human groups need common references, shared phobias and philia, hobbies and hatred, ideal spaces that unite all the members of the group. In French, they use the expression idées reçues, and I would say that tradition can be guessed in the background: these ideas – forgive the clumsy translation – are views and/or opinions that have come to us from the past, from our ancestors.

Mikel Saiz

If the common places that compact a society are usually the heritage of past generations, traditionally accepted ideas are usually the meeting point of the people, and as a result, both of us, the common places and the idées reçues, are irresistible in any human group. Both help us to pave the way and advance, because not having to think about them makes it possible for us to focus our attention on the concerns of others, just as fish move in the sea but do not think about the sea. If we accept what has been said so far, it would seem that, in the event of a change in a society, the first step should be to examine and question its common places, its ideas received.

In its short history, the ideology that dominates Navarre today, that is, Navarre, has had three great victories. The first has been to make Basque patriotism visible as an external force: reading the press, this is the main image in Spain, but this is the point of view that has been and still is quite widespread in Navarre itself. In the 1920s, Navarrese patriots were ordered from offices in Bilbao (according to the Navarrese politician Víctor Pradera), and since the Transition buses full of demonstrators have come from Gipuzkoa (according to the Diario de Navarra).

The definition of Basque patriotism, Spanish, has been the second triumph of Navarrism. That is to say, one can imagine – or at least I can imagine in my xalo – a tolerant Spanish that is capable of respecting the enemy. In our country, however, in addition to promoting the most intolerant Spanish, navarrism has managed to make this the only legitimate form of Spanish. Anyone who moves from there will be immediately accused of trying to join the “outside” forces.

The third victory was the transformation of these last two points into a common place for multiple Navarreses, since the Diario de Navarra has not spent a hundred years in vain. So the trap is done. On the one hand, Basque nationalism is an evil that comes to us from the West and, on the other hand, the ideology that the UPN defends against it is the only legitimate answer. Moreover, this ideology is not ideology, since it is the expression of the character of the good Navarrese. Ollarra, the former director of Diario de Navarra, once said: “I am not a Navarrese, but a Navarrese.” Navarrism, therefore, has become our idée reçue, our particular sea, without being the object of thought –because it does not exist– the unpolluted water that allows our movements.

As the residual elections have made quite clear, it is now necessary to invent a different kind of Spanish in Navarre, one that knows how to respect the diversity of Navarre and, if it is possible to paradox it, is less linked to Spain. What is not so clear is whether those who have to do it are willing to do the work of reinventing themselves. You'll have to see it.

In its short history, the ideology that dominates Navarre today, that is, Navarre, has had three great victories. The first has been to make Basque patriotism visible as an external force: reading the press, this is the main image in Spain, but this is the point of view that has been and still is quite widespread in Navarre itself. In the 1920s, Navarrese patriots were ordered from offices in Bilbao (according to the Navarrese politician Víctor Pradera), and since the Transition buses full of demonstrators have come from Gipuzkoa (according to the Diario de Navarra).

The definition of Basque patriotism, Spanish, has been the second triumph of Navarrism. That is to say, one can imagine – or at least I can imagine in my xalo – a tolerant Spanish that is capable of respecting the enemy. In our country, however, in addition to promoting the most intolerant Spanish, navarrism has managed to make this the only legitimate form of Spanish. Anyone who moves from there will be immediately accused of trying to join the “outside” forces.

The third victory was the transformation of these last two points into a common place for multiple Navarreses, since the Diario de Navarra has not spent a hundred years in vain. So the trap is done. On the one hand, Basque nationalism is an evil that comes to us from the West and, on the other hand, the ideology that the UPN defends against it is the only legitimate answer. Moreover, this ideology is not ideology, since it is the expression of the character of the good Navarrese. Ollarra, the former director of Diario de Navarra, once said: “I am not a Navarrese, but a Navarrese.” Navarrism, therefore, has become our idée reçue, our particular sea, without being the object of thought –because it does not exist– the unpolluted water that allows our movements.

As the residual elections have made quite clear, it is now necessary to invent a different kind of Spanish in Navarre, one that knows how to respect the diversity of Navarre and, if it is possible to paradox it, is less linked to Spain. What is not so clear is whether those who have to do it are willing to do the work of reinventing themselves. You'll have to see it.

Most read

Using Matomo

#1

#3

Mikel Garcia Idiakez

#4

Garazi Basterretxea

Newest

2025-05-21

Ahotsa.info

Basque Language Day in Ribera, first time with great success

The first edition of the Basque Language Day in La Ribera was held on Saturday in Arguedas. Culture, neighbourhoods and festivities were combined in this day that united the peoples of the region around the Basque language.

2025-05-21

Elhuyar

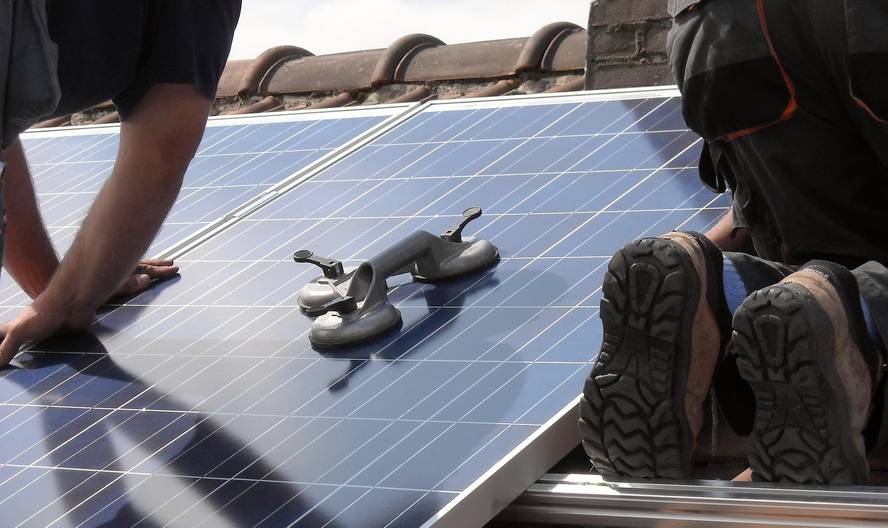

On the rooftops of Vitoria-Gasteiz you can get 38% of the electricity consumed by the city

The UPV/EHU research group Ekopol estimates that by installing photovoltaic panels on rooftops in Vitoria-Gasteiz, 38% of the electricity consumed by the city can be obtained. They came to this conclusion using a high-precision methodology that they have developed.

2025-05-21

Irutxuloko Hitza

Anti-fascist call for Friday

A security rally is planned for this Friday 23rd in the Piedra de Alza Park. Several anti-fascist agents in San Sebastián have denounced that “a follower of Vox” is behind the call, which has also been called by the fascist agents Frente Obrero and Juventud Combativa.

2025-05-21

Unai Lomana Uribezubia

UN warns that 14,000 newborns are at risk of dying within the next 48 hours if Palestine does not receive aid

Israel has imposed a total blockade on Palestine for two long months. As a result, it has not received humanitarian assistance. Israel announced on Monday the entry of five trucks carrying humanitarian aid, after 11 weeks of total closure. Tom Fletcher says it’s just “a drop... [+]

2025-05-20

ARGIA

The Socialist Movement denounces that it has been “denied” the possibility of being put to the beach during the festivities of Bilbao and Vitoria

The GKS of Vitoria-Gasteiz and the Housing Syndicate, and the Luberri of Bilbao, have made an appearance. “For several months” they have assured that they have been trying to “channel the situation” with Bilbao Comparsas and the Txosna Commission of Vitoria-Gasteiz,... [+]

2025-05-20

Xabier Letona Biteri

Civil guards say there was no violence from protesters

On Tuesday, 11 civil guards who attended the second oral session in the Carpinteria’s work area, the vast majority of whom were summoned by the Public Prosecutor’s Office, testified. And compared to yesterday,... [+]

2025-05-20

Unai Lomana Uribezubia

Anti-Cremation Movement Calls for Rally on Saturday to Call for “Stop” Bridge Incinerator

The Anti-Cremation Movement will meet on 24 May at 13:00 in front of the Provincial Council of Gipuzkoa. The Incinerator of Bridges calls on the citizens to join in a meeting to denounce the attitude of public agents and parties to the pollution generated.

2025-05-20

Eneko Imaz Galparsoro

After a two-hour phone call with Putin, Trump says Russia and Ukraine will “immediately” start negotiating a ceasefire

In a message posted on social media, the U.S. president said the conversation with his Russian counterpart “went very well.” Putin has said that efforts to end the war in Ukraine are “on the right track” and that Moscow is ready to conclude a peace agreement with Kiev... [+]

2025-05-20

Jon Torner Zabala

Football stimulus, more private planes than ever in the sky of Bilbao

Every time major sporting events take place, beyond the “economic impact” or “city location” that the authorities are precipitating, it is common to talk about the fierce price of accommodation, its impact on public transport and/or safety issues. It is common and even... [+]

2025-05-20

Unai Lomana Uribezubia

Emergency number 112 recovers after solving Telefónica’s problem

Telefónica has had an incidence and this has affected the fixed network. As a result, the UAE Emergency Management Center has been damaged. However, it has been revealed that the problem has been solved and the emergency telephone 112 is back in operation. It has also had an... [+]

2025-05-20

Eneko Imaz Galparsoro

Seaska denounces that the resources offered by Paris for the next course are not enough

At the opening ceremony of the Popular Step Festival, Erik Etxarte, a member of the Seaska board, denounced that Paris had not yet proposed additional teaching positions for the next academic year. The response of the French Ministry of Education came over the weekend and was... [+]

2025-05-20

Unai Lomana Uribezubia

Man sentenced to sixteen years in prison for raping and mistreating his daughter

According to a court in Gipuzkoa, between 2016 and 2018 she was raped five times and subjected to other sexual assaults and ill-treatment when she was 12-14 years old. The man has been sentenced to sixteen years and three months in prison and has to pay 50,107 euros in... [+]

2025-05-20

Mikel Aramendi

THE ANALYSIS

Mid-term elections in the Philippines: knots exposed

The Philippine political establishment remains today in the hands of some powerful oligarchic clans. And for this reason, the detailed reading of the results has many nuances.

2025-05-20

Aiaraldea

AMA Desoccupa leaves Amurrio without completing the eviction, "thanks to the popular response"

The Air Force Strike Committee (SOS Aiaraldea) reported that the plane was taken back on Saturday by members of the de-occupation company.

Eguneraketa berriak daude

.jpg)