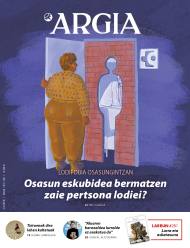

If you don't lose weight, Osakidetza won't insemite you

- Public assisted reproduction units exclude obese women if they do not adjust their weight to a certain body mass index (BMI). It is difficult to question and denounce the legitimacy of this criterion, while the deep-rooted phobia in the health system is not questioned.

Itsaso, Amaia, Miren, Udane and Xare have been treated as fat in Osakidetza when they went to assisted reproduction units. In their testimonies many elements are repeated: they received the order to lose weight drastically, without analyzing their specific health status; they were given comments impregnated in principle; they felt numbers more than patients, and they came crying from the consultation. The analysis also agreed that Osakidetza's priority is not patient health, but saving economic resources, controlling and eliminating inadequate bodies.

Uncontrolled diets

The thick activist Itsaso Ramona begins a process of assisted reproduction to be a single mother. The outpatient gynecologist weighed and did an operation on the calculator: “He told me they wouldn’t inseminate me. I wouldn't get pregnant because of my weight. They have to make sure the treatments are very expensive and they're going to go well. He advised me to lose 20 kilos.” But Itsaso asked him to refer him to Cruces Hospital and the gynecologist said to him, “You have two months to lose eight or ten pounds. Eat well, play sports and return.”

Humiliation and pain were mixed with rabies. They did not consider their state of health and considered that they did not eat well or exercise. “At the time I had the continuation of a private nutritionist. How would you lose 10 kilos in two months if you didn't stop eating? My health cared so much.” He decided to give in: “If the way to be a mother started like this, it would end up resentful and he did not want to create a son in those conditions.” She went to a private clinic and they didn't put obstacles in her. She eventually became pregnant on her own, taking advantage of a boyfriend's son.

Bertsolari Amaia Agirre has experienced a similar situation. Her wife became pregnant with her eldest daughter. The second idea was that the traitor Agirre, but when the gynecologist at Donostia Hospital introduced her weight and height on her computer, she told her she had “morbid obesity.” “The deal didn’t seem right to me. That a woman speaks this way to another woman is very hard, a great humiliation! I could have explained that weight loss would increase my chances of pregnancy, but it threatened me. I asked him if I had to put a gastric ball to get pregnant.” Agirre slows down the eight kilos and returns to age 38. She became pregnant on the first attempt, but underwent abortion. After another four attempts, he gave in and the couple repeated it.

In addition to the Basque Country, ten public health systems in the Spanish State exclude women with high BMI. Osakidetza is not the most demanding: a woman of 1.60 meters must weigh less than 93 kilos (BMI <36) to be able to inseminar in the CAPV and less than 77 kilos for Andalusia (<30). But in this second, the protocol foresees a series of measures: to assess in a personalized way the risks of treatment in patients with high BMI, to give guidelines for achieving a healthy weight and to refer to the Endocrinology and Nutrition consultation. On the Osakidetza website, on the contrary, no reference is made to this, but only the adequacy of BMI is a requirement of access. The Department of Health of the Basque Government has not wanted to participate in this report. The Government of Navarra has not responded to the request for ARGIA and there is no information on the website.

Itxaso Arca, primary care midwife: “The biggest problem is vejatory treatment with obese women. ‘If you don’t lose yourself, we don’t inseminate’ threatens rude and obstetric violence.”

Xare* has a BMI of 40 and has been asking Osakidetza for endocrinological attention for ten years: “The answer has always been that being fat is not a pathology in itself, because I don’t have diabetes or mobility problems, but when I went to inseminar they rejected me for this reason. I know that the Osakidetza service is in a precarious situation, but it is not fair to demand that 25 kilos of weight be lost and that no tools are offered to achieve the goal.”

Exclusion or scientific evidence?

Osakidetza cites the scientific evidence to justify the BMI limit of 36: “Obesity is associated with worse prognosis of assisted reproduction: worse ovarian response, worse follicular puncture, lower pregnancy rate and higher risk of abortion. In addition, obesity-related pregnancy problems are well known: hypertension, diabetes, bleeding, cesarean sections and increased risk of dystrophic delivery (requiring active obstetrician participation), as well as the risk of a macroscopic fetus (fetal development or excessive size).”

Maitane*, an endocrinologist in Osakidetza, has specified the data that corroborate the argument of the service: “Obesity is known to triple ovulatory alterations; premature abortions increase by 50%; it can produce problems in fertilization, in the development and implantation of embryos and is the main factor in the onset of diabetes, including pregnancy. The success rate in fertility treatments is lower and requires higher doses of hormone, which increases the risks of side effects. Consequently, a reduction of 5-10% by weight has been shown to improve fertility in obese women.”

Therefore, this physician considers it appropriate to give a slimming pattern to patients “with respect, without judgment or paternalism”. In other words, he believes that the problem lies not in the protocol, but in the treatment. “Health care must be more humane. Women have the right to all information so that they can decide on their processes.”

Itxaso Arca, a primary care midwife, agrees that “the biggest problem is the vejatory treatment of obese women. ‘If you are not slimmed down, we do not inseminate’ threatens rude and obstetric violence.” It does not deny scientific evidence, but it questions its neutrality: “Prejudice determines what to investigate and what not. Research is aimed at testing a concrete result.” The use of BMI has also been problematic: “Standardizes bodies, does not take into account the existence of different types of bodies. It seems that through an equation we can understand bodies and know their state of health, but it is not true.” The midwife advocates personalized patient care: analytic analysis, asking about her lifestyle and emotional state… “High BMI should be taken into account, not as a tool to judge and exclude patients”.

Marta Busquets Gallego is a Catalan lawyer and activist specializing in maternity. It is clear that it is discriminatory to exclude women with high BMI: “The message it conveys is that some bodies do not deserve the insemination effort of public systems.” But he finds it difficult to win the legal battle because assisted reproduction enters the field of satisfaction medicine: “You cannot deny a coarse person a heart transplant, but one in vitro.”

Thus, if a public service discriminates between people, it should do so according to an objective and rational criterion, which is BMI, although the anti-obesity movement has questioned: “An integrated court in the system will seem logical”. The lawyer has also questioned the scientific evidence used to justify the exclusion: “It is not clear whether elderly and coarse women have worse obstetric results because of their bodies, or how these pregnancies are managed, for example, the tendency to induce their deliveries is evident.”

Busquets and Arca share another argument: obesity can be a risk factor, but there are many other factors that hinder reproduction. Why not exclude women who then live in cities of high pollution, who have taken hormonal contraceptives, who have polycystic ovaries or who have occupational stress? “Because they are considered acceptable. The health system does not like obesity,” concludes Busquets.

Itxaso Arca, primary care midwife: “The biggest problem is vejatory treatment with obese women. ‘If you don’t lose yourself, we don’t inseminate’ threatens rude and obstetric violence.”

She adds that public assisted reproduction centers promote other risks: “Hormones lesbian women without fertility problems, although it is known that ovarian stimulation increases the abortion rate and has collateral damage. This shows that they care about success rates than health.” In this sense, he recalled that the low quality of semen causes obstetric problems: “But the system prefers to make in vitros women with heterosexual partners who inseminate with the son of a donor”. According to the studies, obesity in men harms your child, but there are no restrictions on the BMI of female partners on the Osakidetza website.

All interviewees denounce the hypocrisy of the system: the public health system eliminates obese women, knowing that they will be welcomed in the private sector. Xare said: “Many Osakidetza workers also work in private. There's a business when we go to clinics. Do I have to ask for a loan to pay EUR 8,000 invitations for having a thick shatter? That is, who can reproduce in our system and in what terms?”

Not being able to complain

Xare is the only interviewee who has filed a complaint in Osakidetza, and has also gone to a lawyer to analyze if his case can be prosecuted. Look at Lantz recently identified that the experience at Donostia Hospital was unfair: “I had confidence in doctors. (No) When feminist maternity commented on the topic at the meeting I clicked: that's happened to me, I've been feeling shit."

At 28, she decided to become a mother. She spent two years having sex with her partner without contraception and another year actively seeking pregnancy. Fertility tests showed no problems, although Osakidetza was recommended to go directly in vitro. In the first consultation of the Donostia Hospital they gave him a role with two indications: to stop smoking and lose weight. Remember the physician’s comment: “Summer is a nice time to eat salads!” She weighed 77 kilos and measured 1.70 m; BMI 26.64. Far from the 30 that is considered a barrier to obesity, over 36.

Look did not question the order of slimming, but it took her hard to be demanding with food: “The fertility process is hard. One way to alleviate the burden was to go juerga or enjoy a beautiful meal. He lived a lot, he did everything wrong, he lost opportunities.” When he returned to the clinic, the gynecologist asked him: “You have not slimmed down, that will help nothing.” In the third consultation, when he screamed, he told him that because of the abdominal fat he could not see clearly on the screen the size of the oocytes. She got pregnant on the first attempt.

Obesity can be a risk factor, but there are many other factors that hinder reproduction. Why not exclude women living in high-pollution cities, who have taken hormonal contraceptives, who have polycystic ovaries, or who have occupational stress.

For Lantz it is a new thickening of the health system, but not for activist Udane HerFer, LGTBI: “Doctors have patalized my body since I was young. If I had knee pain, I was told to lose weight.” It is clear that the Osakidetza criterion is economic and obese. He comments that in other countries (Argentina) and communities (Andalusia, Asturias, Cantabria…) a low BMI limit is also established, as thinness can affect ovulation, but for Osakidetza the only problem is obesity. The scientific argument has also referred to a heterosegmental tone: “Surely this type of research has been conducted with women with fertility problems; I had no problem, because I have a female couple who needed a child. I got pregnant at the first insemination with a low hormone. I have not had gestational diabetes or any difficulty.”

Udan goes to the Cruces Fertility Unit at 34. “I was told I was close to work and I was constantly squeezed by expressions like ‘put on the stacks’.” However, when he returns to have a second child, they tell him that he will not inseminar because he has raised eight kilos. It seems absurd to him, but he does not complain: “The stigma of obesity is very large, it causes shame and guilt. If I don’t get pregnant or have an abortion, I think it will be my fault.” He channelled his anger through activism: he organised a round table on this exclusion; Itsaso was the rapporteur, as he denounced Osakidetza’s policy in an opinion article. The thicker will not complain in the health system until the baby is born healthy. “I have a voice that tells me inside: what if they are correct? Have I been irresponsible for becoming pregnant?” She has had an exciting pregnancy from a physical point of view, but she has led her with great discomfort, fearing that something will be constantly complicated.

The midwife Arca knows these fears well: “Obesity in the world of health causes great suffering in women, which seriously damages the life of pregnancy. This negative effect seems to me to be more dangerous than a high BMI.” More than putting the burden of the complaint on women, it has been in favor of the transformation of the medical culture among professionals: “Complaints are of no use while those responsible who value them do not accept obstetric violence and fat deposits. We must work on respect, consensus and physical diversity in outpatient clinics, hospitals and colleges.”

*Names invented at the request of the interviewees.

The pandemic has revealed, in all its crudeness, the consequences of the neoliberal model of care for the elderly, children and the dependent population. Now is the time to consolidate the critical discourses and community alternatives that flourished during the lockdown.”... [+]

You may not know who Donald Berwick is, or why I mention him in the title of the article. The same is true, it is evident, for most of those who are participating in the current Health Pact. They don’t know what Berwick’s Triple Objective is, much less the Quadruple... [+]

Indartsua, irribarretsua eta oso langilea. Helburu pila bat ditu esku artean, eta ideia bat okurritzen zaionean buru-belarri aritzen da horretan. Horiek dira Ainhoa Jungitu (Urduña, Bizkaia, 1998) deskribatzen duten zenbait ezaugarri. 2023an esklerosi anizkoitza... [+]